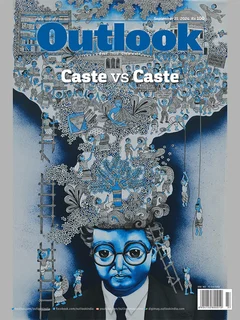

A seven-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court recently suggested that states can now “sub-classify the Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs)” in order to help the worst-off sections within these categories.

A longstanding constitutional directive that earlier identified the uniformity of these groups—based on socio-cultural history, like the clause of untouchability for the SCs and geographical alienation for the STs—has thus been radically altered.

The judges remarked that both categories are heterogeneous as certain sections within them have achieved class mobility by utilising the benefits of the reservation policy. It initiated a heated debate over the idea of social justice, the mandate of the reservation policy and its political fallouts.

The Constitutional Mandate

The modern Constitution makers had sincerely acknowledged that the Brahmanical caste system is the most oppressive order against the untouchable castes. The untouchables and Adivasis were denied basic human entitlements and were forced to survive away from the modern developmental processes. Babasaheb Ambedkar provided the needed mantle to their plight and made them a crucial subject in the nationalist deliberation. He utilised modern political ideas and constitutional identities (like the Depressed Classes earlier and later the SCs) to organise the diverse untouchable castes as a unified national bloc, demanding their participation in the modern institutions as crucial partners. He further proposed Buddhist religious conversion to escape the blot of untouchability, inviting them to join the democratic processes as dignified individuals.

Though Ambedkar’s movement helped a significant section of the SCs to enter into the middle-class domain, the constitutional means were insufficient in bringing the needed social reforms that could alter the conventional class inequalities and caste hierarchies. A vast section of the SCs and STs are still surviving in the most precarious socio-economic conditions. The court has shown sympathetic concerns towards the worst-off social groups. However, its prescription to bifurcate the SC/ST categories appears a knee-jerk reaction to a much deeper question of historical injustices and social exclusion.

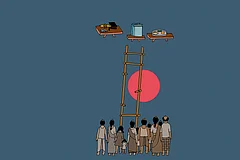

The idea of social justice and its related policies, mainly the reservation policy, has often been misunderstood as being the State’s welfare initiative to introduce a new mobile class among the marginalised social groups. Such superficial remarks about the reservation policy as one of the poverty eradication measures have harmed the values of social justice more.

In the current case, the court also characterised the reservation policy as a job distribution programme for the marginalised castes, neglecting its ethical objective. The mandate of social justice policies is to democratise public institutions by limiting the conventional control of certain social elite groups over the State’s power and privileges. However, any reflection on the implementation of the reservation policy will showcase that only a minuscule section of the SCs and STs have benefitted from the reservation policy, retaining the domination of social elites in government sectors.

The Compromised Agenda

In the recent past, there has been a growing consciousness among vulnerable social groups about their precarious socio-economic conditions and they have demanded effective policy reforms to ensure their equitable participation in the developing economy. The BJP-led central government has not only neglected these demands but also carried out strategic interventions to break the unity of the oppressed groups.

In the 2024 General Elections, it was often analysed that the marginalised social groups were disheartened by the BJP’s unsympathetic attitude, especially in the states of Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand. The SCs and STs in these states did not vote for the BJP but supported the INDIA bloc significantly. It now appears that such a tactical rupture of sub-categorisation is orchestrated by the ruling elites to derail the powerful social movement for social justice.

A vast section of the SCs and STs are still surviving in the most precarious conditions. The court has shown sympathetic concerns towards the worst-off social groups.

The top judiciary decided not to discuss the complex and corrupt implementation process of the reservation policy. Such an investigation would reveal that the presence of SCs in state institutions is overtly negligible in Group A and B posts, whereas they are more segregated into lower positions, mainly in menial and hazardous jobs (like sanitation workers). The idea of a creamy layer among the SCs and STs is therefore a mistaken attribute, as it typecasts or vilifies a small number of beneficiaries as dominant groups that appropriate the reservation policy more than the rest. Instead, the small and reserved category candidates in the state institutions often face discrimination and harassment at workplaces.

The actual socio-economic conditions of the SCs (including the castes that are categorised as a creamy layer) are deplorable and extremely vulnerable compared to the other Hindus.

For example, in Maharashtra, the cases of caste atrocities, violence and discrimination against SCs have doubled in the past decade (1,091 cases in 2012 to 2,743 in 2022). These include the extreme cases of violence and rioting against those from the Mahar caste—the so-called ‘creamy layer’. The caste division between the SCs is meaningless for the general Hindu psyche as for the perpetrators of caste discrimination, the Dalits are overtly looked down as the lowest rung, unfit to enjoy equal social status. The division among the SCs has wrongly manifested that certain caste groups have escaped the Brahmanical caste order and are enjoying the benefits of middle-class status.

Expansion of Social Justice Measures

Distinct from such quick technical solutions offered by the judiciary, the Dalit-Bahujan movements have suggested new momentum and reforms in the agenda of social justice. The immediate need is to revive the agenda of social justice for the SCs and STs by initiating effective welfare measures in the spheres of education, health and other livelihood issues. Such initiatives shall be target-oriented, mainly to improve the socio-economic conditions of the worst-off Dalit and Adivasi groups.

Second, the state and central governments shall showcase their readiness to implement the reservation policy effectively and immediately in all institutions of state, including the fulfilment of backlog vacancies. Third, it is equally required that the social justice policies be expanded in other spheres of the economy regulated by the state, especially in contractual appointments, single administrative posts (like state secretaries and vice-chancellors) and in institutions marked as ‘super speciality’ courses and professions (especially in the medical field or in the judiciary). This will introduce diverse SC/ST groups as a crucial workforce, generating substantive empirical data to showcase diversity among beneficiaries of the reservation policy.

Finally, the government shall initiate effective affirmative action policies to ensure equitable participation of the marginalised social groups in the market economy. It is visible that the representation of the SCs, STs and the OBCs in the private sector is restricted mainly to low-paid jobs, whereas the positions of power and privileges (like the CEOs, top executives, managers, etc.) are dominated by professionals belonging to the social elite strata. It is necessary that the state shall take more initiatives to promote a strong entrepreneurship and business class among the SC and ST groups, making them an integral part of global economic development.

Such expansion of social justice ideals with substantive welfare measures concerning building an inclusive economic order may allow the marginalised social groups to avoid such skirmishes and tensions that occurred due to the Supreme Court’s order on sub-categorisation.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Harish S. Wankhede is a noted scholar and public intellectual, specialising in Dalit studies

(This appeared in the print as 'Slicing the Pie')