During a recent encounter with a prominent Indian photojournalist in Delhi, who, upon learning about my Kashmiri identity, eagerly declared, “Development is making its way in Kashmir.” I listened, patiently waiting for her to finish as she shared that one of her friends working for an NGO in Kashmir had told her so.

“Kashmiri people want jobs and education, and now they are finally getting them,” she continued, eventually asking for my thoughts. I looked her dead in the eye and asked if she had ever heard of the Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali. She nodded yes, and I quoted from one of his poems— “They make a desolation and call it peace.”

Since August 5, 2019, when the Indian government stripped Jammu and Kashmir of its statehood and autonomy by abrogating Article 370 and Article 35A, there has been a notable increase in surveillance and a clampdown on press freedom in Kashmir, and hence, enforced silence, echoing themes from George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984. Orwell’s work, which explores totalitarianism, propaganda, and the suppression of dissent, provides a framework to understand the implications of these measures on journalism and freedom of expression in Kashmir.

Big Brother is Watching

In 1984, Orwell introduced the concept of “Big Brother,” a figurehead representing the omnipresent surveillance state. In Kashmir, the increased surveillance post-abrogation of Article 370 manifests through heightened monitoring of journalists, restrictions, and limitations on internet access.

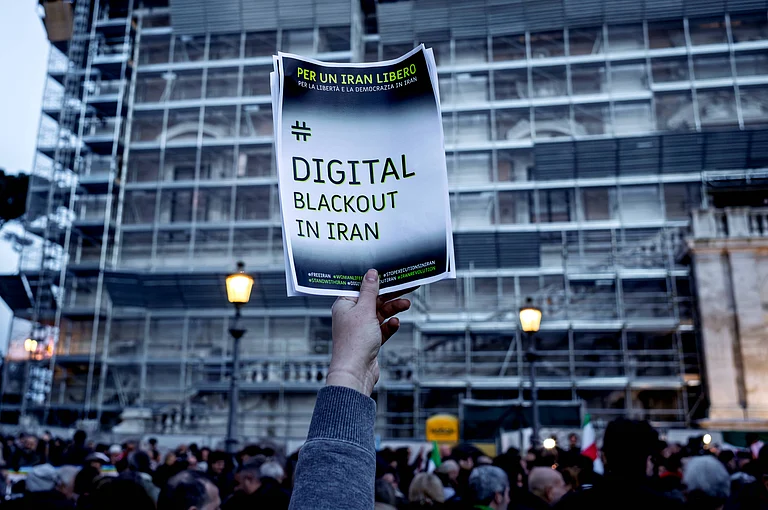

Following the abrogation, the Indian government imposed one of the longest internet blackouts in Kashmir. This move, justified as a measure to prevent unrest, severely impacted the ability of journalists to report accurately and timely. Access was limited and heavily monitored even when internet services were partially restored. High-speed internet was restricted, and social media platforms were closely watched, creating a climate of fear among journalists who might otherwise report critically on the government’s actions.

Since August 5, 2019, when the government stripped J&K of its statehood and autonomy, there has been an increase in surveillance and a clampdown on press freedom in Kashmir.

Journalists in Kashmir have been summoned by police for questioning and asked to reveal their sources. Such actions parallel the Thought Police in 1984, who intimidate and coerce individuals to suppress any nonconformist thoughts. Physical attacks, raids on homes, and the confiscation of equipment further contribute to an environment where journalists are under constant threat, inhibiting free and fair reporting.

The Ministry of Truth

The Ministry of Truth in 1984 was responsible for altering historical records and propagating the Party’s version of reality. This manipulation of information ensured that citizens could only access government-approved narratives, thus manufacturing consent and controlling public perception.

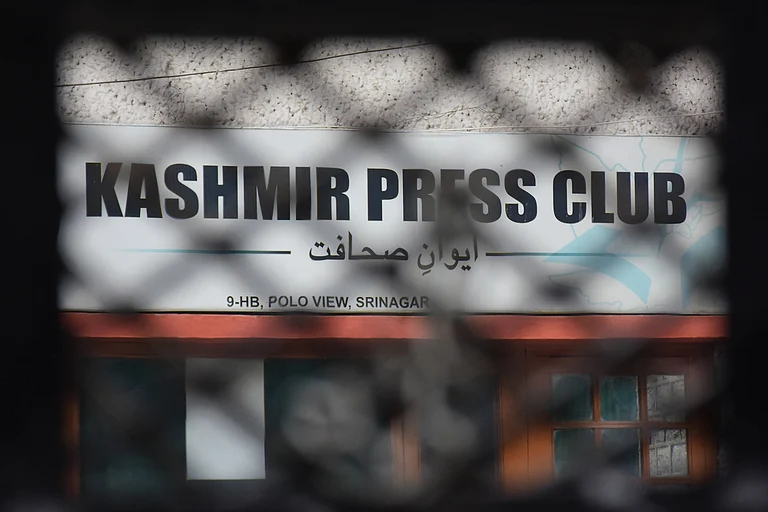

The Indian government has been pushing a particular narrative about Kashmir that emphasises “development” and “normalcy” post-Article 370 revocation. This narrative downplays and dismisses reports of human rights abuses and local dissent. Journalists who attempt to present a counter-narrative face significant challenges, including legal action under stringent laws such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). In fact, the newly created State Investigation Agency (SIA), intended to investigate terrorism cases, has been instrumental in the crackdown and arrest of journalists for “narrative terrorism,” a pattern of intimidation against independent journalists in Kashmir by labelling them as “anti-state narrative builders” and “terrorist sympathisers.”

The SIA is influential in what is termed as the systematic “erasure of memory,” where online archives of local newspapers are disappearing. This erasure, combined with legal harassment and internet shutdowns, aims to control the narrative and obliterate evidence of government abuses to rewrite history and silence critical voices. Thus, contributing to a climate of fear and self-censorship among journalists in Kashmir.

In 1984, the Party also created “Newspeak,” a controlled language used as a tool to limit freedom of thought and concepts that pose a threat to the regime. The goal of Newspeak was to make any alternative thinking or rebellion impossible by eliminating many words from the language or altering their meanings. In 2020, the government introduced a 53-page media policy in Kashmir “for effective communication and public outreach.” They also issued a verbal directive to major newspapers in Kashmir to follow a pre-specified stylesheet, forbidding the use of certain words and terminology that reflect Kashmir’s contested narratives.

The directive instructed journalists to replace the word ‘militant’ to refer to armed resistance with ‘terrorist,’ ‘Pakistan-Administered Kashmir’ with ‘Pakistan Occupied Kashmir’ and ‘militant outfits’ with ‘proscribed terror groups.’

Thoughtcrime and Doublethink

Orwell’s 1984 explores the suppression of dissent through the concepts of thoughtcrime and doublethink. Thoughtcrime refers to unorthodox thoughts that oppose or question the Party, while doublethink is the acceptance of contradictory beliefs, conditioning citizens to accept the Party’s reality without question.

Reporters Without Borders has noted that Kashmir is one of the most dangerous places for journalists. Instances of harassment, intimidation, and even physical assaults on journalists are not uncommon. In such an atmosphere, self-censorship becomes a survival tactic. Journalists often avoid reporting on sensitive issues such as human rights abuses by security forces, political dissent, or separatist activities. I recently spoke with one of my journalist friends working in Kashmir, who described the palpable fear that pervades the press corps there. “Every story feels like a risk,” he said. We have to think about our families and our safety. The threats are real.” He was invited to write about the media clampdown in Kashmir but eventually opted out for fear of retribution. Such actions mirror the persecution of thoughtcrime in Orwell’s dystopia, where even the mere expression of a contrary thought is punished severely.

Since August 5, 2019, journalists in Kashmir have been operating under severe constraints. The threat of surveillance and intimidation is ever-present. The persistent narrative pushed by the state, combined with the harsh consequences of dissent, has forced journalists into a state of doublethink. They must navigate the precarious balance of reporting truthfully while avoiding state retribution.

The psychological pressure of constant surveillance and the threat of punitive action has created an environment where self-censorship has become the norm.

The psychological pressure of constant surveillance and the threat of punitive action has created an environment where self-censorship has become the norm, ensuring that the government’s version of events remains unchallenged. Most of the major newspapers in Kashmir are filled with advertisements. When asked what happened to journalism in Kashmir, an editor friend of mine reminded me that such questions amount to blasphemy in the current scenario.

Digital violence has become a critical tool for the Indian state in Kashmir. The government regularly imposes internet shutdowns, the longest being the 2019 blackout lasting over seven months. Social media, which has become a vital platform for expression globally, is a double-edged sword in Kashmir. While it provides a space for Kashmiris to share their experiences and views, it also exposes them to surveillance and scrutiny by state authorities. Ordinary people and journalists have been arrested for social media posts deemed to incite violence or anti-national sentiment. As a result, many Kashmiris are cautious about what they share online, often resorting to vague or coded language to express their opinions. This enforced digital silence aims to create a facade of normalcy and peace, masking the underlying discontent and state violence.

However, despite the oppressive environment, in between enforced and self-imposed silences, Kashmiri journalists somehow continue to exist like wildflowers pushing through the cracks in the concrete, defying the silence imposed upon them. Many journalists in Kashmir continue to report on the ground realities despite the risks. Their resilience highlights the enduring human spirit and the quest for truth. Amidst the desolation, they find ways to remember, break the silence, and speak.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Souzeina Mushtaq is an Assistant Professor of journalism at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls.

(This appeared in the print as 'Surveillance And Survival')