German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche declared in the 19th century that Christianity and religious morality can no longer offer the organising principles of social life as Christian morality is a ‘slave morality’ of the vanquished, and he went on to ask what can possibly replace God. He famously declared ‘God is dead’ and pleaded for individual ‘will to power’ to replace collective morality. A century later came along French philosopher Michel Foucault, who this time famously declared ‘Man is dead’. He meant ‘man’ or ‘human’ is a social construct of its times and it is futile to attempt to discover an essence. It is a life without essence, and therefore, a life with infinite opportunities to be explored. Foucault’s anti-humanism sounds exciting but restless. There is no place to rest. Can self-discovery and self-reliant individualism provide enough succours in living a life, even if it lays a premium on freedom against imposed moral order? How do we escape collective control without getting reduced to atomised selves?

Both the philosophers could not have predicted an ingenious postcolonial alternative in finding faith in godmen, babas and gurus. God took reincarnation as godmen. Euphoria around the temple in Ayodhya lost steam just a week after the pran pratishtha, but thousands of people thronged to collect the soil on which Bhole Baba walked in Hathras. Gurus animate life and seem to compensate for the disenchantment with the ‘traditional’ God, religiosity and rituals. Modern gurus are more transactional and interactive than ‘waiting for God-ot’.

The 1970s were a euphoric period of revolutionary zeal that was anti-systemic. Systems and regimes were imagined as concrete structures to be overthrown. By the 1980s, we moved to a more sober language of transforming and engineering institutions and reinventing new models of (good?) governance in order to make service-delivery efficient. Efficiency was the new mantra. By the turn of the century, after the rise of a faceless globalisation, there were no identifiable systems to be targeted and it proved futile to tweak institutions, and faceless and impersonal global market processes created their own antidote in foregrounding visible interpersonal interactions and individual choices as the only tangible alternatives left.

Personalised affects influenced democracies, leading up to the rise of populist regimes with an individual leader and his style of functioning as the hallmark of a functioning democracy. Individual leaders took upon themselves to deliver goods and promises, circumventing institutions and procedures. We seamlessly moved to an era of direct democracy and direct cash transfers. It is the pragmatics of immediacy over the nicety of democratic accountability. Many felt it was the rise of the demagogues but the people felt assured by individual ‘guarantees’.

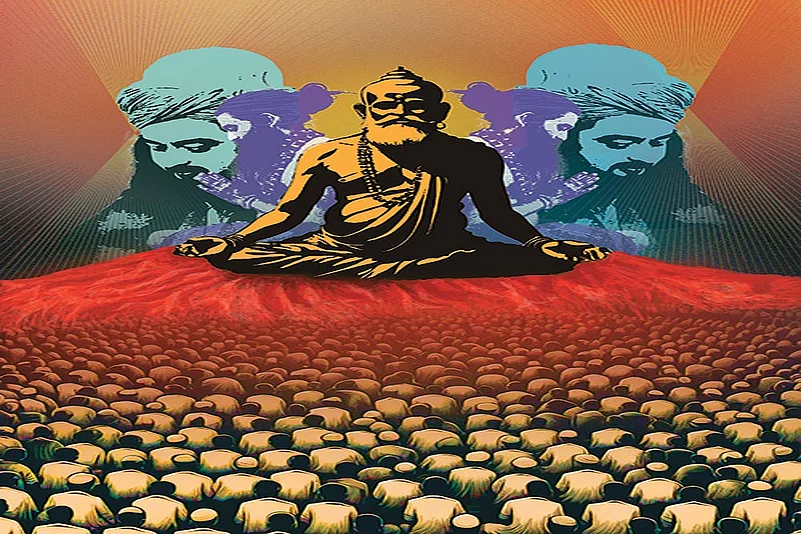

The unprecedented rise of babas needs to be understood in this context. Facelessness of global processes made the formlessness of God less appealing. God in flesh and blood feels more enticing. The euphoric appeal of babas becomes even starker when it’s understood in the context of the fading stardom in Bollywood, the irreverence of politicians and public representatives and the normalisation of the heroics of cricketers and other sportsmen. Public respect of most professions is by and large eroded. Gone are the days when doctors were revered as saviours and life givers—literally, as representatives of God on earth, saving life. We put behind us the days when we placed a teacher, only next to parents. Nothing can generate hysteria. Not even a temple. The hysteria that right-wing masculine leaders wish to generate through the Hindu-Muslim narrative is possibly generated only by the local babas. The intensity of market forces is reproduced in the socio-spiritual domain by new-age babas and gurus. Where do they draw their Midas touch from?

Gurus, through their live gatherings, offer their devotees and followers a real-time experience of getting integrated into larger cross-caste and cross-class communities.

Babas are in tune with the mood of our times. There is nothing magical about it. They are magicians without magic. Godmen have come to the rescue of God. They reinvented him in a world impatient for tangible deliverables. They have restated what works in the real world is what is moral. We need here-and-now solutions. From long and tiring pravachans, today’s gurus offer hands-on solutions. If you are stressed, you meditate; if you are lonely, attend satsangs; if you are bored, gurus can be humorous on the most spiritual of things. Baba Ram Rahim can entertain you with his swanky bikes and bizarre outfits, Sri Sri can dance and hop, Asaram Bapu can spray bubbles and provide reiki, instead of carrying a halo on his head. In Vaitheeswarankoil in Tamil Nadu, there is an entire industry of palmistry. It is believed that Lord Shiva has written down on palm leaves the future of each one of us. If one gets to visit the place, it is visible how good sociologists and psychologists these astrologists are. They understand that most people come with three kinds of problems related to health, wealth and emotions. They take an informed guess, and offer futuristic solutions. Not long ago, Sathya Sai Baba at Puttaparthi in Andhra Pradesh offered gold rings and gold chains to purified ash, depending on the social status of the devotee.

Religion is no longer about fear or salvation, it’s about psychological relief with a ‘value added’ realisation that all relief is temporary and momentary. The intention—saaf niyat—of providing momentary relief is what is so compassionate. Brahma Kumaris speak about karma and getting reconciled to suffering rather than trying to escape from it. It is the futile attempt to escape that is more painful. The more the world around us becomes difficult to cope with, the more we go deeper into our own selves. There is a home within us. Why look for it elsewhere?

Interpersonal ethics have assumed a significant proportion in arriving at ideas of justice and good life. As we zero in on personal ethics to make sense of reality, gurus become the one-stop option to understand how to navigate ethics in modern life. Travis Rieder, in his recent book, Catastrophe Ethics, begins rather dramatically when he writes, “Modern life is morally exhausting. And confusing. Everything we do seems to matter. But simultaneously: nothing we do seems to matter.” He thinks these kinds of moral dilemmas emerged with recent crises like climate change, where every bit of our action matters, but it will eventually make no difference to the catastrophe we are staring at. Its scale may have gone up many times, but this was the crux of myths and mythologies.

Mythologies dealt with how in human life we are always caught inextricably in a bind that is not easy to shrug off. This was what was, perhaps, referred to as a curse. One is under a curse to suffer the inextricability. The best representatives of this in modern times are our mothers at home, forever caught in the cycle of guilt and resentment. If they don’t take up household responsibilities, they are guilt-ridden; if they are overburdened, they resent it. They spend a lifetime living it. In fact, in mythologies, life itself is a curse and we need moksha from it and that is why Ashwatthama in the Mahabharata was cursed with life without death. It is a different matter that western civilisations are in perennial search for immortality using AI and other scientific discoveries. The return to interpersonal ethics is also the story of the meteoric rise of gurus. They epitomise interpersonalism as the only reality out there.

On the social front, caste dynamics have also changed due to the market, globalisation, migration and urbanisation, among other aspects. Caste was seen through the lens of difference. The conventional wisdom was that the more social mobility caste groups witness, the more they will claim their specificity. However, it did not turn out as expected. The more social aspirations are realised, the greater the urge for integration and greater community life than an emphasis on difference. This somewhat unexpected caste dynamics has handsomely helped gurus to gain their prominence.

Gurus, through their live gatherings, offer their devotees and followers a real-time experience of getting integrated into larger cross-caste and cross-class communities. This could be an empowering experience, and match the social aspirations and processes of social democratisation. Gurus are the transmitter belts for actualising the changing caste dynamics. They emancipate stigmatised bodies, momentarily. They liberate marginalised castes from social ghettoisation, just the way malls allow new spaces, where irrespective of one’s economic standing and income, one can be invested in malls, even if it’s only for window shopping. Spirituality no longer requires austerity and asceticism. Spirituality and bullet trains are the new colonial cousins and inseparable as Siamese twins.

All said, as God, gurus too are unimportant; it is the unflinching faith in them that is a significant emotion. We may move on from the era of gurus, but the search for deep faith will continue to haunt us. As boredom and ennui set in with the antics of gurus, the mysticism pales, the guru phenomenon will be passé, but our search for authentic emotions and intimacies will get deeper. The deeper it gets, the more isolated we begin to feel. And that pain will need, yet again, a new name.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print as 'In Flesh And Blood')

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Ajay Gudavarthy is with the centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University. His recent book is Politics, Ethics, And Emotions In ‘New India’