4 August, 2019

It was a sunny day like any other. I was returning to my hostel after classes at my boarding school, which was far from Kashmir. My chemistry teacher had finally been replaced, and I was excited to tell my father the news.

At the warden's office, where we used to make calls, the warden said my cousin Bazzu had already called multiple times. I should call her back, she said. On the phone, when we spoke, Bazzu said, "The internet can be cut off anytime." She said these words with a seriousness that was unusual for her.

All of sixteen, I knew little about Article 370, except that it held some meaning to Kashmir.

“There is a huge inflow of troops, all non-locals have been asked to leave the valley. Clashes and casualties are expected. This could be our last call,” she added.

In the background, I heard other family members talking about getting ration. They seemed to be buying as much food as they could in preparation for the curfew. This was the power of Kashmiri rumours—mostly, they are treated as gospel truth.

My other cousin was trying to complete a download for a TV show before the internet went down. 'With curfew comes leisure, too,' she said from a distance, her phone was on speaker so her hands were free to prepare for the curfew.

"If we die, don't forget us," she continued.

In Kashmir, the unexpected is always around the corner. So I didn't ask questions. Just then, the warden interrupted, saying my phone time was up. I handed the phone back.

Out Of Network Coverage

August 5 was a day of tense anticipation. I couldn't concentrate in class; my mind kept wondering if something had indeed happened in Kashmir. The final school bell had barely rung when I rushed to the warden's office to find all the Kashmiri girls had already gathered, and, like me, were looking worried. We took turns trying to call our families, but every attempt ended with the same note: "The number you are dialling to call is out of network coverage."

“If we die, don't forget us”

My cousin's words kept replaying in my head. I asked Ambren, one of the girls, to join me in the internet room, and we searched for news about Kashmir. We scrolled through a barrage of articles: "India revokes Kashmir's special status."

We exchanged worried glances, but not words. As Nizar Qabbani wrote: “Not everything in the heart can be said, so God created sighs, tears… and shivering hands.”

We then searched for updates on whether the mobile network had been restored, or when it might be. There was no news to find. We returned to the warden's office. Some of the girls did not even know why they could not get in touch with their families—they did not know about the abrogation of Article 370, or the curfew. We told them everything—what happened, and how we were unsuccessful in reaching anyone in Kashmir. All of them burst into tears. Nadya, who normally fought to get more time to talk to her father, was traumatised.

We were not new to curfews, but, that day, being away from our families for the first time, we felt the weight of uncertainty. Our families back in Kashmir perhaps faced one reality, but we thought of many possibilities - and one of them was, would they all be alive?

The uneasiness lingered. We all missed our families dearly. That's how the days passed by. We wanted to be home, with them, facing what they were facing. The words of a story by Gordon Cook and Alan East, from our Class 11 English textbook, resonated deeply: "We're Not Afraid to Die... if We Can All Be Together."

Days Passed By

Now that we got the news of abrogation, we had to live with it. On the bright side, I knew my younger cousins and brother would be happy—no school for them!

I also kept wondering about other possibilities. Would there be months of violence, more funerals? Would the military raid our homes?

I thought of my cousin too. Before that fateful day, she’d been preparing for her wedding, and I was concerned that she might marry without me present. I wanted to tell her not to wear a maroon dress, and instead to go with something lighter.

Days turned into weeks, and still, there was no word from Kashmir. Since there was no communication with families, we started running out of money. We could not buy Butter Maggi and french fries from Pawna, the sole restaurant within our school. We settled for bland food from our school’s mess hall.

Every day, after my classes, I would go to the newspaper room and read the sheets in full. Normally, I would have only scanned the bold headlines and moved on. Yet, after August 5, every day, I was met with disappointment—there was no news.

Why this silence? Does silence mean peace? No it doesn’t.

“They make a desolation and call it peace,” said Agha Shahid Ali in his work The Country Without a Post Office.

“But we joke and laugh otherwise we would start screaming.”

- Charles Bukowski

We were ten Kashmiri girls and we often met at nights and talked about our experience with curfews. For Kashmir’s Generation Z, the most prominent curfew was in 2016, when Hizb-ul-Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani was killed. Our lockdown after that lasted five months. We didn't have school for all these months, and when we finally went back, we were sent to the next grade in a mass promotion.

We bonded over our shared struggles, and found some lighter moments as well.

Ambren, 17-years-old, shared a story about how, when she was 14, she almost got hit by a bullet during a protest that she had been recording on her new phone. An army man cocked his gun in her direction. She froze, unable to move. She closed her eyes, recited the Kalima, and felt like her legs had stopped working. But, when she opened her eyes, the army had used tear gas and everyone was running for cover.

Urooj joined, and shared a joke. She said an army man was once asked how Kashmiris survive curfews without food. He replied, 'When we raid Kashmiri homes, the one thing we always find is man-sized containers of rice!' We all laughed.

It's true—Kashmiris usually store a lot of rice, grains, and medicine at home because we never know when we'll face another curfew.

Reunited By Newspaper

I was reading the newspaper one day in mid-September when a news article caught my eye. Students from Aakash Coaching in Srinagar had been moved to Himachal Pradesh due to the curfew. I immediately thought of my cousin Juggu, who studied in that centre. I had no idea whether she was part of the group.

On the next page, I saw an ad for the institute along with a phone number. I decided to try my luck. I borrowed a phone from the warden's office and dialled the digits. I reached out to the Delhi centre, and they connected me with their Himachal branch. I was put on hold multiple times before I finally got the girls' hostel’s number.

This was my chance to know if everything was okay at home. A lady answered, and I asked to speak to my cousin Juggu. She said she will check the register. Then, the words I wanted to hear: "Yes, she's here. Let me call her."

When my cousin came to the phone, I felt a rush of excitement and blurted out, "Jugguuuuuuu!" Our voices entwined in a mix of laughter and tears. We talked about everything and nothing. Our conversation flowed effortlessly.

Juggu told me she was fine; However, because of the communication blackout, she had no idea about the state of my family or any of our other relatives. She described the eerie atmosphere; the army patrolling the streets everywhere; she had no idea about anything happening outside her house.

She told me about a brief moment of joy she experienced at the Chandigarh airport: her phone showed 4G connectivity. “But WhatsApp was empty. All the Kashmiri contacts had August 5 as their last seen." she said. It was as if we had vanished in to thin air, she added.

We had a long conversation about the curfew and our careers. It was a good day.

First Landline Call

By the end of September, newspapers said landlines in Kashmir would be functional again. We started waiting to hear from our families, and it didn’t take them long to contact their cut off children

One evening, the warden told me I had a call from home. I rushed to answer it. The elevator was unavailable, so I ran down the stairs instead.

When I got to the phone, my mother was on the line. "Hello?" I said, trying to stay calm. She said, "We're all okay, don't worry." She was calling from the police station, where a lot of parents were waiting to talk to their children, so we didn't have much time to talk.

"Are you eating well?" she asked. I said yes, and that was it—our call finished within a minute. But just hearing her voice made me feel better. I was thankful to God. Sooner or later others got the calls too. We were all relieved to know our families were safe.

Welcome To The Paradise

In October, our vacations finally started, and our parents came to take us home. We were overjoyed to see each other after such a long time. I made sure to exchange contact numbers with my friends, hoping that postpaid SIMs would be functioning soon. Usually, postpaid SIMs were used by the army and so we expected that they’d start working sooner.

At the airport, I used the time to download games on my father's phone. I downloaded a dress-up game with which I used to be obsessed, a car racing game for my brother, (which he later said was useless), and many other things, including a book. This was my stock for myself and my siblings, to keep us occupied.

For the first time, we didn’t sleep on the plane because we were excited to see our home. The flight felt longer than it usually does.

As we landed in Srinagar Airport, the iconic sign Welcome to the Paradise on Earth never felt more misleading. Just outside the airport, there were rows of giant, green army trucks, concertina wires and many checkpoints.

An army convoy passed by so we briefly stopped our car. Amidst all this, the weather was so pleasant—neither hot nor cold, but perfectly beautiful. The air was crisp and clean, a welcome respite from Delhi's suffocating pollution. Perhaps, I thought, this is what they mean by Paradise—not the absence of conflict, but the serene mountains and pleasing weather.

Books And Bluetooth

As I returned home, my cousins gathered around, eager to share their stories of life under the lockdown. They recounted the moment they heard about Article 370’s abrogation on TV. The Home Minister's announcement in Lok Sabha had left everyone shocked and saddened. My aunt had burst into tears, saying, "They've taken even this from us."

In the days that followed, the streets had been empty and the army was everywhere. I wanted to know how they passed all these days.

My sister had found escape in Notes from Underground, an existentialist novel she'd bought long ago. But she never had the chance to read it because she had schoolwork to complete. So, when the curfew started, she finally picked it up—and now she's read it three times. She said it's not a book you can appreciate in a single read, and that this was the perfect time to read it over and again. I guess reading about someone's existential crisis must be a good distraction from life under curfew.

One of my cousins said she had started downloading a Pakistani drama, but just as she was downloading the second last episode at midnight, the internet connection went out. To this day, she wonders if the drama had a happy ending.

I also heard an interesting story about offline movie sharing. A neighbour, who had returned from Delhi, had a few movies on his phone and shared them with my cousin via Bluetooth. My cousin then shared them with others offline, and by the time the curfew restrictions were lifted, almost everyone in town had watched the same movies. As they joked, "Whether or not we had internet, ‘Bluetooth' was our curfew saviour!’

Children Of The Curfew

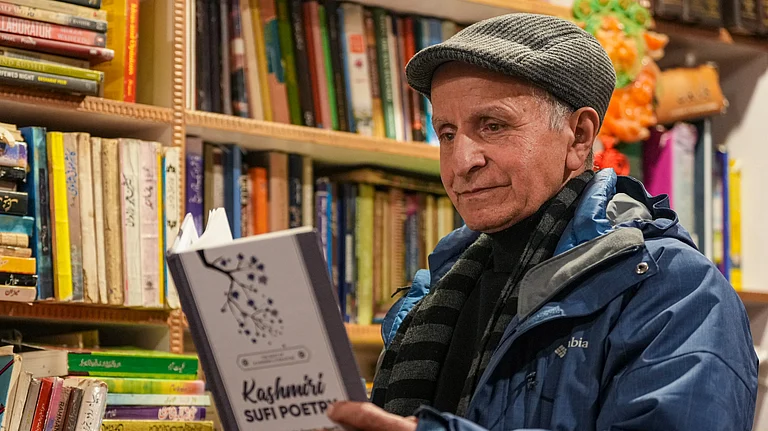

This is my story of the days during the 2019 curfew—an experience that wasn't new to us, and perhaps, won’t even be our last. We were born into curfew, raised under its shadow. From our grandparents, we inherited not only the poetry of Habba Khatoon and Lal Ded, but also the stories of militancy and military. As we grew older, we learned new words like fake encounters and custodial disappearances.

The absence of curfew sometimes feels abnormal. Children going to school every day, something taken for granted in other parts of the country, looks almost out-of-place here in Kashmir.

With time, we have found ways to cope with life under curfew, with no internet, no connection to the world, and no vegetable markets or grocery stores open. We have learned to live within a quiet home and stare at an endless blue sky above.

(In order to maintain anonymity, people’s nicknames have been used.)