The five-vehicle convoy meanders through the dusty, potted tracks before coming to a grinding halt in front of a school at Begampurva in Kanpur. Attired in a kurta and pajama, union minister for coal Sriprakash Jaiswal ambles into a dingy room along with a few Congress workers to address a motley group of people, mostly Muslims. But, Jaiswal allows his supporters to do the talking while he remains stoically seated, a characteristic feature of his campaign as he defends his parliamentary seat in Kanpur a fourth time.

“Do not let the secular votes split. Jaiswal has done a lot and will continue to be there for you. You saw how the Samajwadi party government abandoned Muslims during and after the Muzaffarnagar riots,” a Congress worker tells the people, before asking Jaiswal to speak. Jaiswal’s aphoristic appeal, laced with a smattering of Urdu and a bit of humour, lays stress on development, and betrays the fact that he is up against a formidable opposition—senior BJP leader Murli Manohar Joshi.

Having won the Kanpur parliamentary seat thrice in a row, Jaiswal is battling anti-incumbency, which he denies that it even exists given his claims of development work, charges of not having done enough for the city, possibility of a split in minority votes and a veteran BJP leader, who is a seasoned campaigner having united the fractious city unit of the party. However, the Congress leader is not a pushover. Having got a head-start in the electoral fray, Jaiswal began campaigning long before the opposition candidates could get their act together. A local candidate, he knows the terrain well.

“Joshi is an outsider to Kanpur and this factor will work in my favour,” says a combative Jaiswal, while refusing to consider the veteran leader as a redoubtable adversary. “People are satisfied with the development work and it will beat any anti-incumbency here,” he said.

But for every Jaiswal supporter one finds in town, there is another ready to launch a vituperative attack on the Congress leader. Says Saurabh Srivastava, a BJP supporter, “Jaiswal did nothing for Kanpur. The M.G. Road was built at a cost of Rs 12 lakh some time back. Look at its decrepit state now,” he says. Accusing the Congress MP of being publicity hungry, Srivastava says, Kanpur saw development only when the BJP was in power—both at the centre and the state. “Look at Surat where women, bedecked with jewellery, can walk safely at night. I hope a BJP win will offer such security to Kanpur,” he said.

However, Jaiswal blames successive state governments in UP for having stymied many of his developments schemes for Kanpur—once known as the Manchester of the East due to hundreds of factories and industrial units dotting the city’s landscape.

“Power supply is erratic, and we need someone who can deliver on the electricity front too,” says Ramendra Trivedi, who works in the private sector. Jaiswal, though, faults the SP and BSP governments for having ignored the electricity woes, despite his numerous appeals for their cooperation.

The cavalcade reaches Bakarganj where Jaiswal prefers meeting with people during a 5-minute padyatra in the bylanes of the area. His campaign revolves around padyatras and people-to-people contact which, according to his supporters, have endeared him to the people.

"Accessibility is a factor that will work in his favour. Every Saturday and Sunday he is in town, meeting people and solving their problems. He had helped me once, too," says Mohmmad Shamim, an auto driver. Jaiswal has a clean track record that will help him fetch votes this time as well, he says.

However, such claims fail to rub off on the opposition candidates who launch a broadside on Jaiswal for his role in the coal scam. Branding him as the "hero of the coal scam", Samajwadi Party candidate Surendra Mohan Agarwal alleges the union minister did little to alleviate the poor infrastructure. It pays to have an MP from the party in power in the state, he says, adding that with the SP in power in UP until 20017, people in Kanpur will vote SP to have perfect coordination between the city MP and the state government. "Development needs money, and money can come only from the state government," Agarwal says.

Jaiswal was at his lethal best in Daboli where he launched a vitriolic attack against his opponent—this time by name. "Ask any friend or relative in Varanasi about Joshi's development work, and if he is satisfied with the work carried out there, then please vote for Joshi and not me," he thunders. He rubbishes charges of corruption against him. Not long after his sententious speech got over, his supporters distributed pamphlets highlighting development works carried out by Jaiswal in the city.

The city's complex population dynamics have often baffled poll analysts. Once a bastion of the RSS, the city also has a high density of labourers, who have voted for different parties in the last several decades. The decline of industries has been a sore point with the labour population and traders alike. "For every seed to grow, it needs a conducive environment. Kanpur does not have it anymore to sustain industries," says AK Sinha, secretary, UP Merchant's Chamber.

Santosh Tripathi, a former associate professor of political science at DAV College, says, "The mixed religious population and easy accessibility will work in Jaiswal's favour." Also, the OBC votes and support from traders will be crucial for Jaiswal, he says. However, Joshi will bring about massive consolidation among the 28 percent Brahmin population of the city, while uniting the many warring factions in the city BJP. "He is a heavyweight with a long and distinguished career that makes him a powerful foe," he says.

Besides the Brahmin factor, Muslims too will play a decisive factor in the evenly poised contest. "Comprising about 30 per cent of the city's population, Muslims have voted Congress in the parliamentary polls, and the SP in the Vidhan Sabha polls," Tripathi says. The Congress managed to win only one of five Vidhan Sabha seats in the last state elections, he points out. The Muslims are being courted by the SP, too. "The Congress is a sinking ship, while it's only Mulayam Singh Yadav who is fighting Modi. The BSP has allied with the BJP several times in the past leading to Muslim disenchantment with them. Muslims will only vote SP," says a combative Agarwal.

With an aim to woo the minorities, AAP has fielded a renowned surgeon, Dr Mehmood Rehmani, while the BSP has given ticket to Salim Ahmed—both Muslims. Though both parties are being bracketed in the also-ran category, they have the potential of denting Congress prospects. Not all Muslims will vote for a candidate who stands the best chance of grounding the BJP. Says Mohammed Junaid, who owns four auto-rickshaws in the city, "We must give Modi a chance, after all he talks development. What happened in Gujarat is past. I will vote for him." Price rise can be controlled through peace and stability; no Hindu or Muslim wants riots, he says.

The Muslims tend to decide whom to vote for only a day or two before elections; community meetings in mosques and homes coming into play at the last moment, said a local Congress leader, who wished not to be identified. But Jaiswal is hopeful of a last-minute consolidation in his favour of the torrents of anger among the Muslims against the Samajwadi Party government for its alleged role in the Muzaffarnagar riots turning into streams of humanity casting their ballot. "Every secular person will vote for me," he avers.

As the winds of change blow across the city, there are many who would vote for the candidate perceived strongest. "There is a saffron surge and many people will vote for Modi, even though they may not have personal preferences for him," says Manish Saraswat, an employee of the Indian Air Force.

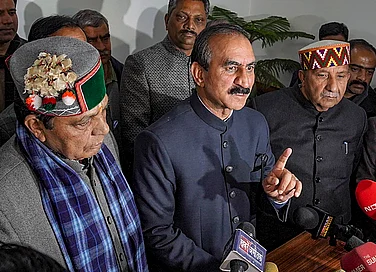

Under Siege

Sriprakash Jaiswal fights a fierce battle for survival against Murli Manohar Joshi in a city whose complex population dynamics have often baffled poll analysts

Under Siege

Under Siege

Published At:

MOST POPULAR

WATCH

MORE FROM THE AUTHOR

×