Earlier this year, a friend sent me a packet of peppermint cigarettes called Phantom and for a dislocating second, I was twelve again. Sticks of white peppermint with one end painted red; that was meant to be the smouldering tip. I used to smoke them in middle school out of a red-and-white packet that looked vaguely like a real cigarette brand called Red and White except for the Phantom’s head crudely printed in the centre. I bit off an end and I was home. Every childhood has its madeleine and this was mine.

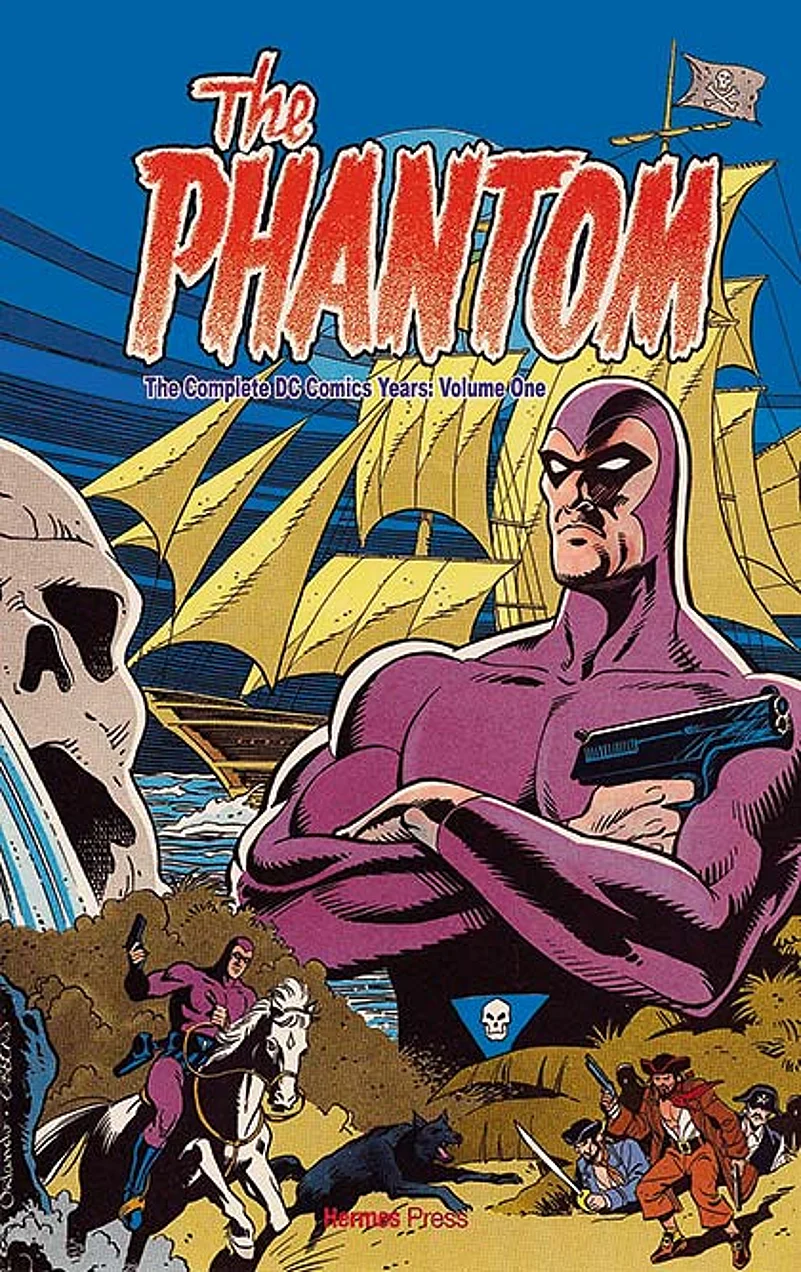

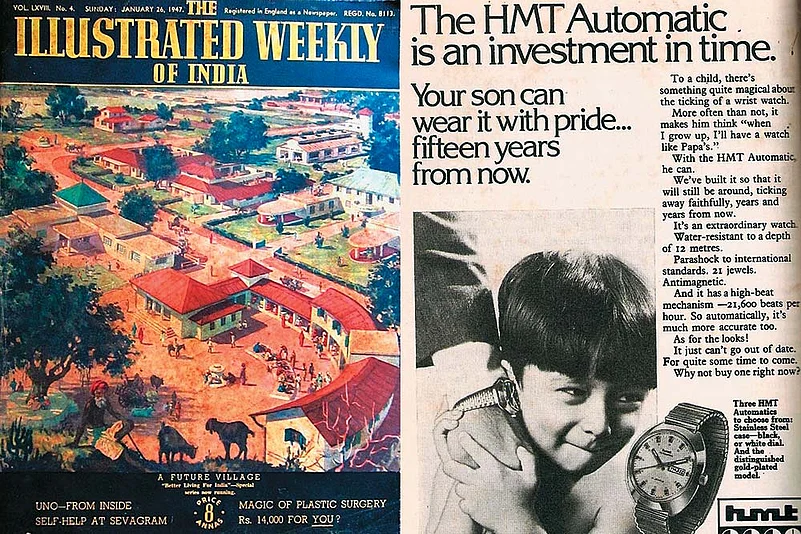

Nostalgia needs absences and that packet fairly thrummed with vanished vibrations. There was the Phantom, aka the Ghost Who Walks, who hadn’t had an outing in years. The periodical in which his adventures used to be serialised, The Illustrated Weekly of India, India’s ur-magazine, had been dead for nearly three decades, killed off by Samir Jain in 1993 along with Dharmyug. Just to say the names is to name the dead. There is something right about the fact that the Weekly died soon after the economic liberalisation announced by Manmohan Singh in the summer of ’91; it died with the India it used to illustrate.

It’s sobering but true that our individual affection for the good bits of our past isn’t particularly individual, it is a kind of herd remembering, the curated slobber of an ageing generation. This doesn’t mean that our fondness for the past isn’t rooted in experience, merely that nearly all nostalgia consists of lowest common denominator memories, polished into radiance by endless fingering.

The ganne ka ras vendor with his hand-cranked crusher, endless iterations of Bapsi Sidhwa’s ‘ice candy man’, Jean Junction denims with kolhapuris to match, Keventer’s cold milk at DePaul’s, the morning show (reduced rates) at Rivoli (or Odeon, Regal, Plaza or Golcha, fill in the blank), ice cream evenings at India Gate, ‘ganjing’ down Hazrat Ganj, pastries at Fleury’s, being a tourist on Marine Drive, looking sideways at naked white people on Anjuna beach, these are at once vivid personal recollections and a cohort’s sedimented self-image of itself.

For those who came in late: The crime-fighting Phantom was the original superhero.

What’s wrong with that? Nothing, except that it’s so stylised that it’s often incomprehensible to others. The obvious example of a collective yearning for a vanished past is Ostalgie, the longing, part ironic, part deeply felt by former East Germans for their vanished Communist homeland after the reunification of 1990. This had something to do with the economic costs of integration into West Germany.

East German women, particularly, used to being part of the workforce, lost their jobs disproportionately as unemployment rose, and the healthcare and childcare that had been a given in the Communist state, shrank. The fact that Soviet-style communism was both oppressive and economically unsustainable, didn’t stop a generation that had known nothing else from missing it and its artefacts, like the clunky Trabants that had clogged GDR’s streets.

There is a distant family resemblance between Ostalgie and the curious nostalgia for the involuntarily austere India that existed before liberalisation. Viewed from a certain angle, autarkic India can be claimed as a simpler, less ‘consumerist’ place, simply because there wasn’t that much to consume. The affection for cars like the Ambassador and the Fiat preserved in a time warp by an entrenched duopoly, is a nostalgia for a world where car radiators smoked under propped up hoods, where holdalls were strapped to roof-clamped carriers, where a family train journey meant ‘coolies’ and monstrous luggage.

Some part of this nostalgia in my generation had to do with the notion of self-reliance as import substitution. HMT (Hindustan Machine Tools) was, in effect, a national champion and its watches weren’t just watches, they were emblems of economic independence. We didn’t like the fact that everything imported looked better than everything locally made, but the latter had an unexpired alibi: it was Made in India.

Time Capsule: When the Illustrated Weekly and HMT were household names

But much nostalgia is merely perverse. One of the things I remember most clearly as a teenager is taking six empty milk bottles in a wire frame carrier to the Delhi Milk Scheme depot in the neighbourhood. Along with the bottles, I used to carry a rectangular aluminium token that was a license for getting the bottles refilled. A queue would form at 4 pm outside the wooden box that housed the milk booth and through its tiny window, empty bottles would be exchanged for full ones sealed with foil caps.

And the foil caps were beautiful! At a time when everything was crudely packaged, these metal caps fitted the mouths of the milk bottles like they had been born with them. Depending on whether you were buying full cream, or toned or double-toned, the colours of the caps varied from blue, to striped silver-and-blue, to silver. I hated the business of queuing up for milk. It was time taken away from reading fiction or doing nothing. It’s not the tedium that I hanker after; it’s the finish of those foil caps and their promise of perfection.

The real difficulty with middle-class nostalgia in India in the early 21st century is that it looks back fondly at a time when Indians were, in absolute terms, worse-off than they are today. Middle class civil servants, for example, lived their lives on seemingly tiny salaries, but they lived them in spacious, subsidised sarkari bungalows arranged around parks, little Edens tailor-made for their children’s recreation. And they were serviced by servants (not staff, not help, but servants) who worked for food, a servant’s quarter and a derisory salary: a full-time cook in the mid-1960s was paid thirty rupees a month.

White Americans, like the New York Times’s columnist David Brooks, hark back to the 1950s as a post-war golden age. White South Africans (who invented the shopping mall) probably saw the 1960s as a kind of master race heaven. The fact that both countries in their different ways were deeply segregated societies, asterisks the nostalgia for those decades. It’s possible for an American to think of the 1950s as a work in progress, to find solace in the fact that the second half of the century saw the rolling back of several forms of institutionalised racism. That’s impossible for the white South African; the destruction of his world was a precondition for the construction of a racially inclusive South Africa.

ALSO READ: Our Past In The Present

One way in which India’s educated ruling class justified its privilege was via the narrative of political inclusion and democracy. The epic narrative of a dirt poor, short-lived, illiterate people, bootstrapping its way into modernity via universal suffrage, served us well; it made nostalgia plausible because it was a powerful story that was partly true. But now, as economic growth slows and as India mutates into a majoritarian state, the justificatory stories that we told ourselves to burnish our youth, are hard to believe. Once, we assumed, self-importantly, that we’d leave our children our memories and an India better than the nation we found. All we can hope to leave them now, as Philip Larkin once wrote of another country, is money.

(This appeared in the print edition as "NOSTALGIA: The Ghost That Walks")

ALSO READ

Mukul Kesavan teaches history at Jamia Milia Islamia, Delhi