It was only 11 a.m. but Mr Sastrigalapuram Subrahmanya Ramaswamy Iyer felt ‘brain fatigued’ already. He could not figure out these fancy management consultant fellows, with their complicated jargon, Americanised accents and fancy PowerPoint presentations. This team from Blackthorn Consulting was merely the latest in a series that he had met with in recent months—McKinsey, Bain, BCG, among others—each one more talkative and theoretical than the last. And what astronomical rates they charged, ayyo swami! He had been against calling them in, but his younger son, Cheenu, had insisted. What to do?

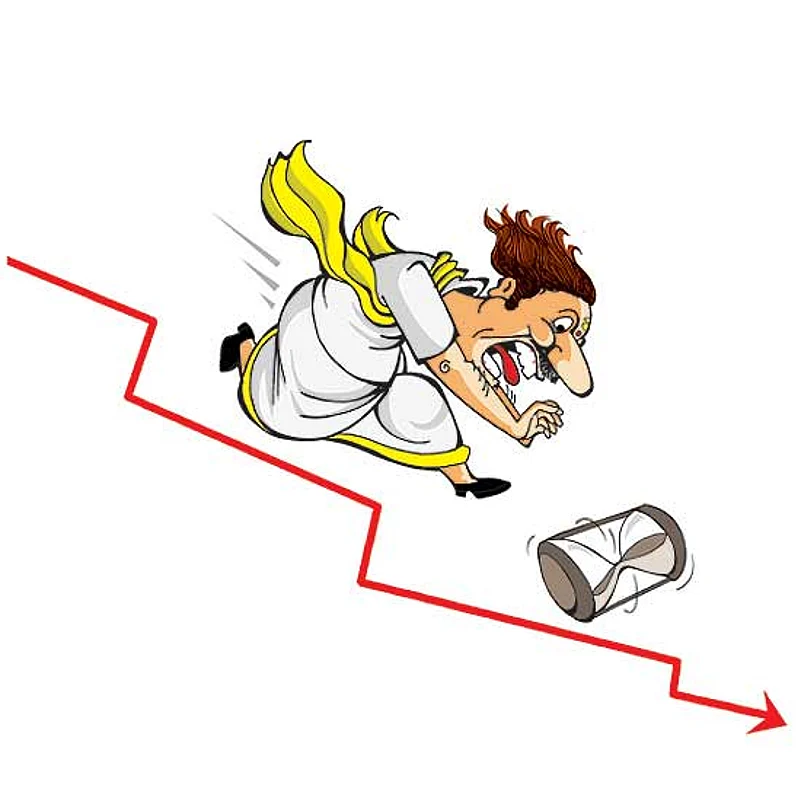

Mr S.S. Ramaswamy Iyer was the chairman of the YesYes Group of industries, and he had always prided himself on his approach of simple living and Iyer thinking. As someone once remarked, looking at his crisp white veshti and shirt you could not tell the difference between him and his driver (unless, of course, you happened to notice the gold Rolex peeping out discreetly from under his shirt-cuff). Ten years ago, his YesYes Group had been one of India’s leading industrial giants, held in high esteem for the quality of its automotive products and responsible, largely, for making sleepy Chennai the “Detroit of India”. But since then, its fortunes had skidded: its growth rate had dropped to the single digits, its market cap had stagnated and it had been overtaken by a series of rascal fellows whose names he had never even heard till a few years ago. It seemed to be a case, as Spencer Johnson would have put it, of ‘Who moved my cheese?’ Or, rather, ‘Who moved my uthappam?’

Mr S.S. Ramaswamy Iyer sipped his second cup of filter coffee of the morning and frowned. He really couldn’t understand it. YesYes products were still first-class; its ethics were the stuff of industry lore; its staff and dealer network had, over the years, become almost a part of his own extended family; its management, headed by himself and his sons (educated at Wharton and Kellogg, mind you), was prudent and respected. And as his grandfather used to say, quoting his mentor, T.V. Sundaram Iyengar, “If you sell a product for Rs 10, your customer should believe he has got Rs 11 worth of value. But it should have cost you only Rs 9 and eight annas”. A very wise business mantra, indeed. One that had helped keep YesYes at the top, decade after decade, but which had now suddenly stopped working. And God only knew why.

God himself might not know, but this fellow from Blackthorn—chit of a chap, could not be a day over 40—claimed to know. He spouted out pieties, like “The biggest risk is not to take a risk” and “Fail fast, fail smart”, at the drop of an angavastram. Damn fool, was it his investment that was at stake? Or his good name, built up so carefully over the years? This morning he had started the session by reminding the YesYes directors that the latest Forbes list of billionaires included 55 names from India, but only 10 were from the south—five of which were from Infosys, and four from first-generation businesses. The point he was trying to make was how the old established business houses of the south were falling behind in terms of market cap, but Mr S.S. Ramaswamy Iyer had a different takeout. He shuddered. Forbes list of billionaires? How shameless! God forbid that he—or any member of his family—should ever be mentioned in such a list, for all the world to see.

And then, before you could say Shankarabharanam, those wretched Blackthorn fellows had launched once again into one of their discourses on Ansoff matrixes, PESTEL analyses and corporate re-engineering. What did they really know about his business, anyway? It had taken Mr S.S. Ramaswamy Iyer himself nearly forty years, on the shop floor and in the marketplace, to finally master its secrets. No, frankly, the only consultant he was prepared to listen to was his trusted financial advisor, K.K. Murugan, of Murugan Stanley—and sometimes, in times of necessity, Vaidyanathan, his old family astrologer.

Coincidentally, at that very moment, in other conference rooms in the South, similar PowerPoint presentations were being made by strategy consultants to other old-line Chettiar and Brahmin companies, like Mettupalayam Motors, Pudukkottai Pistons, Gummidipoondi Gear-boxes and Tirukalikundram Tractors, not forgetting Chinglepet Chemicals—trying to convince them to address the very same set of problems: conservatism; low risk appetite; hierarchical thinking; failure to professionalise sufficiently; insufficient investment in R&D and sticking to corporate comfort zones. And, not so coincidentally, those PowerPoint presentations were received by their clients with similar degrees of scepticism: kindly excuse. We’ve seen the cost of excessive corporate ambition. We’ve watched what has happened to our good friends in Andhra Pradesh, for example. And we’d prefer to stick to our strengths, manufacture good, solid “things”, and nurture healthy—if unspectacular—balance sheets. We would no more tinker with our time-tested business formulae than we would our grandmothers’ handed-down-for-generations sambar recipes.

But then, somewhere else, a very different breed of new south Indian businessman was quietly plotting the next grand step of his grander strategy. Young D.K. Dhananandam of the Galacticaa Group had no use for the McKinseys and Bains of the world either; indeed, he could teach them things that Harvard Business School could not teach them in a hundred years. He had started out by developing a business structure that was breathtaking in its simplicity and elegance: his father was a key minister in the government, his father-in-law was a leader of the Opposition. So no matter which way Porter’s Five Forces would play out in the foreseeable future, his Galacticaa Group was completely de-risked, leaving him free to wheel, deal, lubricate, armtwist his way through the economy as he pleased. Nobody ever moved Dhananandam’s curd-rice; he moved theirs.

As a result, Dhananandam now figured conspicuously in the Forbes list of billionaires (no unnecessary shyness for him in this respect). And Galacticaa’s enormously successful business interests now spanned all the four elements—Air, Earth, Water and Fire—like the 2G spectrum that he had picked up at bargain-basement prices, the extensive mines that he had cornered, the under-sea gas reserves in the Bay of Bengal that he had been smart enough to get his hands on and, of course, his flourishing entertainment empire, all fire, passion and drama.

In the words of Yeats, “A shape with lion body and the head of a man, /A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun, /Is moving its slow thighs..../ ... what rough beast, its hour come round at last,/Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?” If, in his younger days, Dhananandam had paid attention during literature class at Pachaiyyappa’s College, instead of bunking lessons to swagger around with the Party cadres, he might have recognised those lines. But then, who needs Yeats when you have got (into) Forbes.

(Anvar Alikhan is an advertising professional who writes on various issues, but usually in a sober, respectable manner).