Satya is 20 years old and there is much talk about it in the past few days in the media as well as social media. Friends, students and colleagues have shared some of the pieces on it with me. It is fascinating to see a film one has been a part of become a classic before one’s eyes. This can only happen after a certain period elapses, of a decade or two. Most films are judged within a week, in the binary terms of the box-office—a hit or a flop. Some films last longer and then they are deemed successful. But when a decade or two pass and you still recall a certain film because of the impact it had on you and no comparable film came in that intervening period that could rival the experience of this film, then it becomes a classic of the genre. Satya seems to have acquired that stature. I want to share my memories of working on this film. I’ve not done it so far.

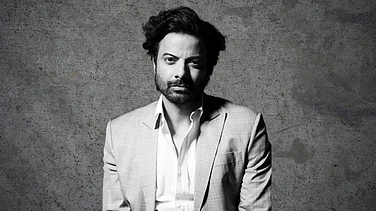

I was not in Mumbai when I was offered work on Satya. I was making my documentary films, travelling to different parts of India. I had seen Rangeela and liked the spirit of it. So I was interested when the opportunity came to work with Rangeela’s director—Ram Gopal Varma. My name had been suggested to him on the strength of a short Marathi film, Chakori, that I had shot, soon after graduating from FTII (Director Shekhar Kapur had liked this work a lot.) Ramu was a great admirer of Bandit Queen, but he was still making up his mind. Then came the phone call asking whether I would join the team of Satya.

There was also Gerard Hooper, an American, suggested by a common friend who was in the US. My friend, an IITian like me, had studied film with Gerard. I had gone on to study film at FTII. Eventually, we both ended up doing the cinematography of Satya.

I relocated to Mumbai and started work. The guerrilla style we adopted for Satya has a background to it. I came from FTII where I had studied cinematography and had experimented particularly with available light photography and fast emulsions in my final year. I had also assisted the veteran cinematographer R.M. Rao in ad films. I felt that genre offered sufficient resources to achieve a desired look. But when it came to working independently, I chose to work in a completely different style in my documentary films. And I was constantly thrown into situations where there was no option but to shoot on the run. Ramu was very open to these methods and gave us a free hand. Since Gerard too came from a documentary background, we were not too divergent in our views.

Gerard was there for six weeks, on leave from work in the US. The shooting took place for about four weeks, but not in one continuous schedule. After about a month, he had to leave as he had a commitment to resume a teaching job at a university. Much of the film was yet to be shot. I took over when Ramu asked me to, after a break of a few days, which was common in those days—films were rarely shot in one schedule. Shooting resumed with me at the helm and went on for at least another six months, with several breaks in between. Ramu was very supportive when I took over. I remember the hush on the set in one of the initial days, when I did the lighting of the scene where Aditya Srivastava is questioned by his superiors about his conduct during Satya’s escape from the cinema hall. Amidst the lull, Ramu quietly came near the camera and looked through the viewfinder. He could feel the atmosphere that the low-key lighting had created. I knew at that moment that I had won the director’s confidence. He was so deferential during the entire shoot that I was touched. One day, when I was shooting the jail sequence with Manoj Bajpayee, I saw a DoP on the sets who had worked with him on his previous film. Later, I came to know that Ramu had told everyone that I work with very few lights and this had made them curious.

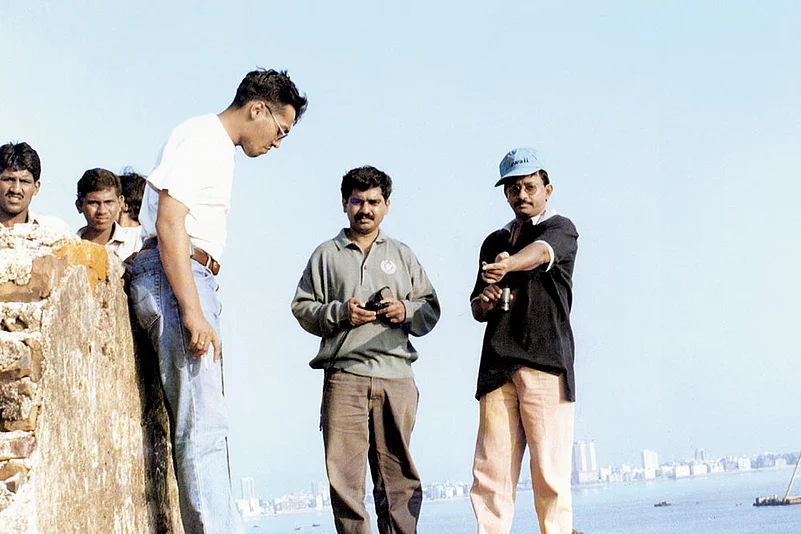

I remember shooting the scene that is often played now as the film’s definitive clip, where Manoj’s Bhiku Mhatre shouts Mumbai ka king kaun? from a city cliff. I tried many camera positions with Ramu before settling on the final one. Now, we came to know that Manoj has a fear of heights. He had a tough time reaching the chosen spot which had a sheer drop. One saw his remarkable dedication to acting then, as he fought off the paralysing fear and delivered the lines with such bravado.

(From left) Anurag Kashyap, Mazhar Kamran and Ramu planning the ‘Mumbai Ka King Kaun?’ scene

Another memorable scene is the blackmailing of the music composer, played by the late Neeraj Vora. It was shot on a night shift in a bungalow at Juhu. I finished lighting by about 11pm. In the scene, Manoj and Chakravarthy arrive in a Maruti Omni and talk to the music composer, threatening him to sign Urmila as a singer or else.... Before they leave, to make their point clear, they fire shots at the window of his bedroom. The glass shatters, he shakes and shivers and they drive on.

I remember I took the pains to light not only the bedroom but also the road below where the gangsters stop their car. When the shot was over, I think in the second or third take, Ramu said pack up. I was surprised. We still had time. I suggested we take a few more shots, it is all ready—“we can quickly take a cut of the two gangsters on the phone”. Ramu was clear. He didn’t need it. He said, “if it has to work, it has to work as a single shot”. That was a something to be learnt, his discipline in shot taking. Never once would he take a second option, an alternate shot. Later, when I was shooting Kaun (1999) with him, he was still the same; there was Zen in his decisions.

I filmed the shootout on the railway bridge without any lights (the entire sequence that begins in an apartment complex and ends on a bridge). We waited for the right moment—when a local train passed in the frame. The energy during the scene was electric. It’s also my favourite scene.

The Kallu Mama song was where I did my unusual experiment. I used 100 watt tungsten bulbs to light up the place. So when the lamp shade was hit in movement, the swaying light created a natural effect. Also, it gave tremendous freedom to the actors to walk around and improvise. This was a time when DoPs would put chalk and tape marks that actors had to hit for getting the focus right and to catch a certain light. I hope the actors still remember this gesture that I did to enable them to do what they liked, without any restrictions or fussing about tape marks.

Shooting a film song was a new experience. I appreciated the technical expertise of the Mumbai choreographers. Here, I resisted the temptation to change the style and tried my best to stay in the genre. But, admittedly, some of the Hindi film song style did creep in. That’s the nature of the song genre. Yet, I made quite a few, rather radical, departures. I remember the shock on the faces in the unit when I said I will shoot Urmila on the beach at Chowpatty without any lights.

This helped create a certain ease on location and we were not mobbed as we did not look like a big film crew. The same guerrilla style came in handy when I and Anurag rushed into VT station and grabbed a few quick shots, of Satya’s arrival into the city, before anyone could notice.

When the film was over, I graded the first copy with a seasoned colourist at Adlabs. It was all analogue in those days. I was the privileged one to see the first copy first, all by myself in the lab’s preview theatre. As I came out, I saw Ramu walk in with an assistant. I was probably beaming with delight at the first look because I remember Ramu saying to the assistant, “He has never looked so happy before. I think we have a good film on our hands” (or words to that effect, I am quoting from memory of course). Then he asked me how it was? I said the film is just rushing along, it has amazing energy. “We will show them,” he replied. This was also part of his attitude. He probably wanted to prove to the world that he still had it in him (after the failure of Daud (1997) perhaps).

There are many more such accounts to give. I remember Ramu saying that the kind of focus with which my camera crew was working helped him focus too, as he had never worked with this kind of discipline before.

Notes from Mazhar’s DoP diary

There are so many untold stories in cinema that one likes to share with the world. As a cinematographer, one is in a unique position to observe a film take shape before one’s eyes...and lens. This is the reason I learnt cinematography: in order to learn filmmaking. In the analogue world, the mystery of this process was greater as the image was seen only by the DoP and the director. That mystery is important in filmmaking.

I am indebted to RGV for giving me the crucial break with Satya and also his next film, Kaun. We went our ways after those two. My next notable film would launch a newcomer director, Sujoy Ghosh, with Jhankaar Beats (2003). The last time Ramu remembered me was when he wanted to shoot the promo for Ab Tak Chappan. He called me to shoot it and I worked with him, Shimit Amin and Nana Patekar. Later, Shimit offered to edit the promo of my directorial debut, Mohandas (2008), as a return gesture.

I am currently at IIT Bombay, teaching film-making and world cinema. I like the academic world because I love reading and teaching just as much as I love making films. I spent my formative years at IIT and returning there is somehow deeply satisfying. I continue to engage with the film world and I’m venturing into independent cinema, that digital technology has enabled. It is possible to tell stories in new ways with new technology that does not require huge resources. My adventure with tech and cinema continues as I explore the ‘camera-stylo’ style (camera-as-a-pen style) that the director Alexander Astruc wrote about much before the French New Wave transformed filmmaking.