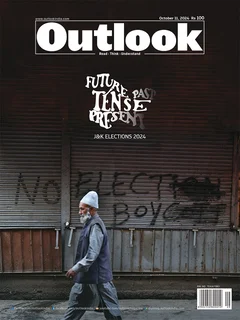

This story was published as part of Outlook Magazine's 'Future Tense' issue, dated October 11, 2024. To read more stories from the Issue, click here.

As the sun rises over the Harmukh mountains in Bandipora, a cavalcade of cars arrives at the shrine of legendary Sufi saint Aham Sharief. A man in a white pathan suit wearing dark glasses steps out of his Pajero and enters the shrine. When he emerges, he zooms off to the block office at Bandipora main town. The crowd there goes ecstatic, chanting, “Teri jaan, meri jaan... Bandipora ki shaan, Usman, Usman.”

It is Usman Majeed’s nomination filing day for the Bandipora seat where he is contesting the assembly election as an Independent. He has won from Bandipora twice and earned voters’ trust by keeping most of his campaign promises of revitalising the region’s economy and providing infrastructure development. On the campaign trail, he stresses that Bandipora will reach “new heights of development” under his leadership. This is Majeed’s sixth electoral contest. The former militant turned Ikhwani (counter-insurgent) turned politician’s first electoral foray was in 1996 as a candidate of the Jammu and Kashmir Awami League, founded by counter- insurgent leader Kuka Parray. Majeed first became an MLA in 2002 as an Independent from Bandipora, and bagged the seat again in 2014 as a Congress candidate. He was also a Minister of State in the Congress-PDP J&K government in 2006.

Majeed’s rise in Kashmir politics is intriguing considering he was once an active militant fighting for Kashmir’s azadi and then a part of Ikhwan in 1995, the pro-government counter-insurgency militia. Some of the Ikhwanis were surrendered militants and the rest were recruited by the State to counter militants.

Majeed started out as a key member of the Jammu and Kashmir Students’ Liberation Front (SLF), led by Hilal Beigh. The SLF later formed an alliance with Ibrahim Mushtaq Abdul Razzaq Memon aka ‘Tiger Memon’—one of the main suspects in the Mumbai bomb blasts of March 1993 that killed over 250 people and injured over a thousand. Majeed says he had a personal bond with Memon as well as a connection to Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). This was probably why he was once vice chairman of the United Jihad Council (UJC), an umbrella body of militant groups responsible for carrying out attacks in Jammu and Kashmir.

In 1989, like many youngsters in Kashmir, Majeed too decided to fight for Kashmir’s azadi. He took up the gun after his “political hero” from Handwara, Abdul Ghani Lone, alleged rigging in the 1987 J&K assembly elections. Lone’s thunderous speech at Aragam village had a huge impact on young Majeed. “It was said that one political party had been given leverage over all others by New Delhi. We thought Pakistan would help us in our fight for independence,” he remembers.

In the summer of 1990, Majeed was back in Kashmir as an SLF “guerrilla”. Soon he was appointed district commander of the organisation for Baramulla. Two years later, he was arrested by the Army’s RR unit from Sumbal’s Sonawari at Hajin. By then he had become “disenchanted” with the tehreek (movement). He felt that there was no end to the bloodshed in the region. Majeed spent about 28 days in Army custody. Meanwhile Beigh’s men took a few top government officers captive and demanded that five of their men, including Majeed, be released in exchange for the hostages. By that point, Majeed’s feelings about azadi had changed. “I understood that India was not about to pack its bags and leave Kashmir,” he says. “Pakistan was not going to go to war on our lines. It was chaos we Kashmiris were getting consumed in this war.”

As Majeed was “fed up” with militancy, he was in touch with “some men”—probably from the country’s security apparatus. “You can call it a sort of relationship...One day, I saw an officer at my village in a one-ton vehicle. He looked smart and dashing to me,” he says. Majeed was hoping to find some respite for Kashmiris from unending bloodshed. However, a few men in his organisation became “wary” and suspected he was working with the security forces. In 1993, he got a directive from Hilal Beigh to meet him in Bangladesh, before heading for the base camp in POK’s Muzaffarabad. Beigh had set up a new militant organisation called Ikhwan-ul-Muslimeen (Muslim Brotherhood).

Majeed reached Dhaka and met with Beigh and a few others. The group wanted to go to Karachi via Nepal and Bangkok, but their passports generated suspicion at Dhaka Airport and they were jailed. “Pakistani agencies got us out of jail and we fled from Bangladesh,” he says. Later, Beigh explained the rationale behind launching the Ikhwan-ul-Muslimeen to Majeed. “We were told we had to train Tiger Memon’s men at our own base camp for a series of bombings inside several Indian states. The idea was to hit India where it mattered rather than a pointless war in Kashmir,” Majeed says.

He started to collect funds for the organisation. Within a few months, Ikhwan-ul-Muslimeen’s office in Muzaffarabad expanded. Being a fitness enthusiast, Majeed added a “decent” gymnasium to the office. One day in 1993, while he was working out, he saw a burly man donning boxing gloves and heading towards him. The “guest” demanded a contest. A short bout followed at the end of which Bandipora’s Majeed knocked down “Tiger” from Mumbai. Later, the two men became friends owing to their “shared enthusiasm for fitness”.

Disenchanted with the tehreek, Usman had his own reasons to return to Kashmir. He says that Pakistani politician Sardar Abdul Qayoom, who had returned from a conference in Casablanca on Kashmir, played a huge role. “Qayoom had a heated exchange with Dr Farooq Abdullah over Kashmir,” he says. Qayoom told him that “Kashmiris are a big bunch of idiots who have set their own house on fire for fighting our war. Instead, you should save yourselves.” These words pierced Majeed’s heart like a dagger. Other factors which added to his disenchantment with Pakistan was ISI’s Colonel Asad Durrani, the man who had initiated Kashmir’s azadi campaign during General Zia-ul-Haq’s time.

Majeed also had an argument with the then ISI officer General Liaqat Ali. “As vice-chairman of the UJC, during a meeting in Rawalpindi, I questioned Pakistan’s Kashmir policy,” he says. “Ali replied that the mujahideen’s job was to prick India just enough to make it bleed, but not enough to make it attack Pakistan back.” Majeed walked out of the meeting and faced a backlash. A friend in the Pakistani establishment informed him of a threat to his life. So he left the country to never return again.

Before leaving Pakistan, he did meet Tiger Memon one last time in January 1995. The “two buddies” had a lavish dinner in a Karachi hotel. “We were quiet...We knew each other well,” says Majeed about that final meeting.

Back in the Valley, Kuka Parray's Ikwans had become a powerful counter-insurgent force. “Ikhwan within one year of its inception had wiped out militancy from Kashmir’s landscape to a large extent. Ikhwanis were the eyes and ears of the establishment at that time,” says Majeed.

After being with the Ikhwan for a year, he joined Kuka Parray’s political party, Awami League, and contested Assembly elections in 1996. Several other Ikhwan commanders too entered mainstream politics at this time. Over the years, Majeed has become a key figure in Kashmir’s political landscape. “From Deve Gowda to I.K. Gujral to Atal Bihari Vajpayee to Manmohan Singh to Narendra Modi, I have met all the prime ministers,” he says.

Like several Kashmiri politicians Majeed terms the decision to abrogate Article 370, which had given Jammu and Kashmir special status), on August 5, 2019 a “harsh” move for Kashmiris. “You love your land. It is something very dear to everybody,” he says.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

A shorter, edited version of this appeared in print