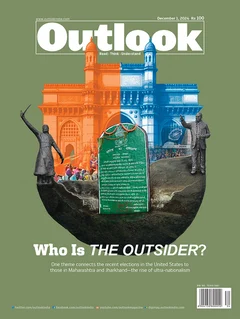

Shivaji, the much-revered Maratha king, makes an appearance every election season. However, this time, it’s the collapse of the 35-foot Shivaji statue in Sindhudurg in August that has been at the centre of much political slugfest. Intertwined with the controversy is Marathi asmita (pride).

After the collapse of the statue months ahead of the assembly elections, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said to the people of Maharashtra: “I extend my apologies to all those who worship Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj as their revered deity. I know their sentiments are hurt.” Modi, who is not known to provide explanations, leave aside offering apologies for any happening under his watch, understood the gravity of the situation.

Shivaji is celebrated as an icon of the Hindu right. He has become an increasingly central figure in Maharashtra’s politics and no political party can afford to ignore him or be accused of insulting him. After all, Marathas dominate the political landscape of the state—12 of the 20 chief ministers since the state’s formation have been Marathas.

The Opposition and the ruling BJP tried to draw capital out of the incident. Modi criticised the Opposition for not expressing regret. “Our values are different. For us, nothing is greater than our deity,” he said. The Opposition, in turn, demanded Chief Minister Eknath Shinde’s resignation, alleging corruption in the statue’s construction. The members of the NCP from the ruling coalition took out a silent protest march.

While the Congress targeted the BJP and termed the collapse as an unforgivable insult to the revered Maratha warrior, Sudhir Pathak, the former editor of the Marathi daily Tarun Bharat, believes the party continues to pay the prize for what Jawaharlal Nehru did. “Nehru in his writings did not use very flattering words for Shivaji. No political party can afford to be seen as indifferent or critical of Shivaji. It directly affects Marathi asmita,” he says.

History speaks of how Shivaji ignited hope among Hindus at the height of Mughal rule in India. “Hindu-Muslim was the only binary and Shivaji taught us what could be achieved if all Hindus united,” explains Prabodh Vekhande, a Marathi scholar and historian. “He was a leader with vision and foresight and believed that Hindus can reach a pinnacle of growth and development if they agree to stand united. What makes him great is that he led with character and courage. There is not a single slur on his personality,” he adds. Shivaji passed away in 1680 and for the next 100 years the Peshwas continued to rule across India. “The forts and the Navy created by him remained a wonder for all. He created a sense of tremendous pride in being a Hindu and coined the phrase Hindvi Swarajya,” says Vekhande.

The Shiv Sena, a major player in Maharashtra politics, owes its existence to Marathi asmita and the symbolic representation of Shivaji. The party has its roots in the 70s movement to protect the rights of mill workers, and those of the quintessential Marathi manoos (common man) whose jobs were taken away by ‘outsiders’, mostly South Indians. It was also the era of Varadarajan Mudaliar, a once-upon-a-time Mob Boss of Mumbai, and the influx of men who migrated to Mumbai from his native place (Tamil Nadu).

“Balasaheb Thackeray spearheaded the movement to drive the outsiders out and reserve jobs for Mumbaikars. The movement spread up to Nashik and right into the Konkan regions, but not beyond that,” says Pathak. “Riding on it, they could capture the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) and, to date, have a stronghold on it as they are seen as the original keepers of the Marathi asmita,” he adds.

“Marathi asmita was a lot about Marathi culture and language, which was predominantly controlled by Brahmins. Today, in Maharashtra politics, Brahmins don’t matter at all as it is dominated by Marathas and OBCs”.

There is little doubt that whenever a political party is floated in Maharashtra, it takes Marathi asmita as its central theme, feels Mukund Kulkarni, a senior journalist and scholar. “The Shiv Sena evolved around the issue of asmita and protecting the interest of Marathi manoos. When Raj Thackeray floated his Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) party, he launched a campaign against people from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar and called them outsiders. Now, Manoj Jarange Patil has conveniently twisted Marathi asmita to Maratha asmita just to garner support,” says Kulkarni, while terming it as a bad move.

He rues the fact that asmita is now divided into castes. “Marathi asmita was a lot about Marathi culture and language, which was predominantly controlled by Brahmins. Today, in Maharashtra politics, Brahmins don’t matter at all as it is dominated by Marathas and OBCs,” he adds. The concept of Marathi asmita existed only in Mumbai and the Konkan region. “Marathwada was under the rule of the Nizam while Vidarbha was a part of the Central Provinces and Berar province, which included Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh,” says Kulkarni, while explaining why it doesn’t extend to the entire state.

Marathi asmita also extended to language. “Unfortunately, nobody takes any pride in speaking Marathi. Maharashtra has a rich culture of saints and Shivaji would bow before all saints. This sense of pride in language was dominantly among the Brahmins. Over a period, there was a demand to declare it as a classical language by people like Mahatma Phule, Shauji Maharaj and Babasaheb Ambedkar. By declaring Marathi as a classical language, it has been taken away from Sanskrit and Brahmins,” feels Vekhande. He adds: “I don’t think this asmita sentiment should be encouraged. Hindutva is a far bigger concept, while Marathi manoos and asmita is confined to Mumbai.”

Over time, Marathi asmita and the protection of interests of Marathi manoos have got diluted. “The term pardesi, frequently applied to non-Maharashtrians, was first used for people who came from Sindh. Before partition, Karachi was part of the Bombay presidency. Sindhis arrived in Bombay after partition and lived mostly on the outskirts of the city in ghettos they created for themselves. Migrants from UP and Bihar arrived in search of livelihood and took up jobs and businesses, which Maharashtrians were not willing to take up. But all that has changed and now they are all a part of our diverse demographic,” says Vekhande.

These migrants made Maharashtra not just a multi-linguistic state but also a prosperous one. It was born to be a linguistic state, and Maharashtrians had put up a relentless fight, and lives were sacrificed for the cause. They fought to retain Mumbai and prevent it from being an independent state or going away to Gujarat. However, over a period of time, Marathis in Mumbai became a linguistic minority.

The campaign to ensure employment for Marathi manoos has also petered out over the years as many Maharashtrian job seekers have migrated elsewhere in the country or flown abroad. In the rest of the economic sphere, the taxis in Mumbai are driven by people from UP. They are also the ones who mind horticulture in Nashik. The dairy industry is dominated by Biharis. The Sindhis and Punjabis run grocery stores. These people have mingled into the mainstream, and their votes have been tapped for political gains.

The split in the NCP and the Shiv Sena has once again revived the issue of Marathi asmita this election season. Both Sharad Pawar and Uddhav Thackeray, who lost their parties and election symbols to breakaway factions, are now seeing an evil design to crush the Marathi identity by targeting regional parties. Supriya Sule, the NCP (SP) MP from Baramati, termed the loss of the party and symbol as a conspiracy against Marathi manoos. “What was done to Bal Thackeray’s family has now been done to Sharad Pawar,” she remarked.

Leaders of both the NCP (SP) and the Shiv Sena (UBT) planned to raise the issue of regional leaders being targeted. “The splits in both the parties within a year was seen as an attack on the state’s leaders. This issue would have gained traction, but it waned as Jarange Patil began his stir for Maratha reservation,” says Kulkarni. “The OBC versus Maratha rift is dominating the rural areas and the issue of regional identity can be invoked now,” he adds.

With so much happening in the Maharashtra election conundrum, the issue of Marathi asmita is certainly in a state of toss and churn.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Barkha Mathur is a Nagpur-based journalist and author

(This appeared in thr print as 'pride over prejudice')