In Housefull 4, actor Nawazuddin Siddiqui plays an exorcist called Ramsay Baba. I watched the Akshay Kumar-starrer and realised just how much my maternal family—the Ramsays—has contributed to Bollywood.

The Ramsay name is synonymous with horror and the paranormal, and has frequently been mentioned across films. To be remembered over decades as the pioneers of horror in Bollywood is a testimony to the Ramsay achievements. The Ramsays have often been tagged as ‘B-grade’ filmmakers, but theirs was a purposeful endeavour to make films for the masses and on a limited budget; they never claimed to be making classics. They wanted people to experience fear through their films, and they wanted to make money while doing this. When they started, they could not have imagined that their films would eventually gain such a cult following. Unfortunately, most of the brothers and their father passed away before they could see the renewed interest in their trademark genre—horror. The surviving ones have the same question on their lips, “Why the interest in us now, after all these years?’”

ALSO READ: Horror As The Theme Of Our Lives

The answer to that question is fairly simple. As my mother proudly used to say, “In Hollywood, horror was Hitchcock and in India, horror was the Ramsays.” That statement holds true even today.

The Ramsays were unique in their approach and vision of films. In their early years of film-making, the whole family went on a holiday to Kashmir and lived on a houseboat for over three months. Under the strict supervision of F.U. Ramsay (hereafter, F.U.), the sons got a crash course in various aspects of filmmaking, a skill they taught themselves and furthered by studying The 5 C’s of Cinematography by Joseph V. Mascelli. It was a rigorous exercise, but it paid off. Over time, depending on their interest, each brother was assigned an area of expertise by their father. That is how the ‘Ramsay Brothers’ were born.

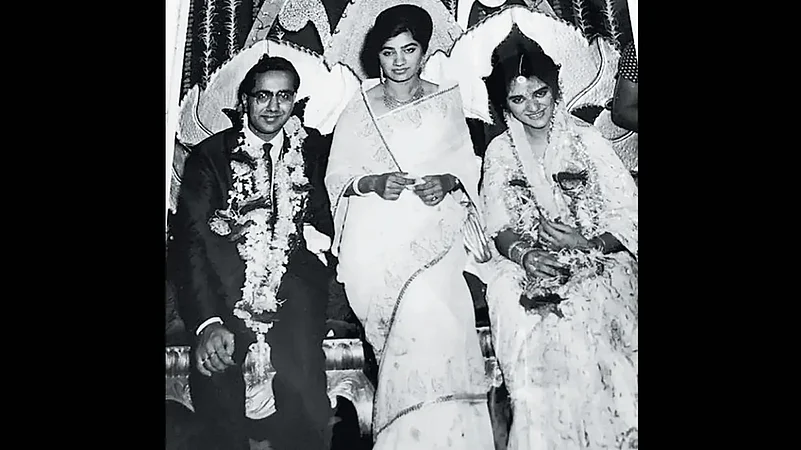

My mother, Asha, is Fatechand Uttamchand Ramsay’s daughter, sister to the Ramsay Brothers. Their original surname—Ramsinghani—was shortened to the easier-to-pronounce ‘Ramsay’ for the benefit of their British clientele. After Partition, the family moved to Mumbai from Karachi and my grandfather, F.U. Ramsay, who was a radio engineer, continued dealing in electronics. My mother, then a little girl, would watch him work, soldering the pieces of a Murphy radio together. Sometimes, he would look up and tease her, play-acting like he was going to jab her with the solder. She would shriek in fear. That was a special game between the father and daughter.

The radio business was changing, so F.U. secured an agency from the Binny and Co. brand and began selling fabric. It was a large household to run, with many mouths to feed—Kumar, Kamla, Gangu, Tulsi, Maya (known as Asha after marriage), Arjun, Keshu, Shyam and Karan. There were seven brothers and two sisters. My mother, Asha, is the younger of the two. Then there was Gopal, another Ramsay brother, who was born after Gangu and passed away as a toddler. Sati, too, a sister born prior to Asha died within a week of birth. Like many small businessmen in those days, my grandfather was drawn to the film industry and wanted to make movies. The fervour of Partition was still in the air, which led to the patriotic Shahid-E-Azam Bhagat Singh in 1954. This was followed by Rustom Sohrab in 1963, the result of Kumar Ramsay’s fascination with the classic Persian legend. Both films clicked at the box office.

The 1970 film Ek Nanhi Munni Ladki Thi became the turning point in the Ramsay’s filmmaking business. While the movie did not do well, both Shyam and Tulsi noticed the audience’s positive reaction to the scene where Prithviraj Kapoor wore a scary mask. It was clear that being scared was a thrill for the audience. Based on this, the two brothers convinced their father to make a horror film. F.U. was ready to give up on the risky business of films but he gave in to the enthusiasm of his sons and supported their idea. Each one of them was trained in an aspect of filmmaking, making them a formidable and self-reliant unit.

The first attempt of the brothers was a Sindhi film called Naqli Shaan. A year later, in 1972, they made Do Gaz Zameen Ke Neeche, the production that finally steered them to their destined genre of horror. The rest is history.

I am often asked, “What was it like to be a grandchild of the Ramsays, where horror was my playground?” My mother used to take us to visit my nana and nani (grandparents) on Saturdays. My mamas, mamis (maternal uncles and aunts) and cousins lived together at Lamington Road in Bombay. My grandparents would be sitting on their individual beds, which were joined at the head in the narrow room. On seeing me, my grandmother would delightedly greet me with her characteristic hearty laugh and draw me into a warm hug. Then she would untie the knot at the end of her sari to give me some money from her hidden stash. I would bashfully refuse, even though I secretly wanted to grab the notes. She would then squeeze the money in my eager palm. Later, I would jump onto my grandfather’s bed. He would ruffle my hair, planting an affectionate kiss on my cheek. As I grew older, the kiss was replaced by a gentle hug.

With the money my grandmother had given me, I would buy a variety of sweets and wrap a mixture of them in paper. Along with my cousin sister, who was my partner in crime, we would run down to the office and sell our version of ‘paan’ to my indulgent uncles for one rupee a packet. They would look up smiling from their animated discussions and rummage for change in their pockets. At the end, I always made a profit and went home with double the money. This was my ritual for years on end.

ALSO READ: The Ghost As A Metaphor In Bengali Cinema

Another memory I have of those days is being assigned the task of tearing open envelopes in the buzzing office at Lamington Road and arranging the contents neatly. The envelopes contained photographs and letters from aspiring actors and actresses wanting to be cast in a Ramsay film. My cousins and I would enjoy discussing the merits and demerits of the aspirants and their entreating requests. Most of them were from small towns, looking for their big break in Bollywood—youthful men with Rajesh Khanna-like haircuts striking a pose; young women wearing skimpy dresses, looking seductively at the camera in the hope of being a heroine or perhaps even a cadaver in the next Ramsay movie. It was a tad pitiful, because even to our immature minds, most of them would not make the cut. The elusive dreams of stardom were flippantly strewn across that desk.

ALSO READ: The ‘Spirit’Of Filmmaking

There was a portion of the office, which was always fascinating to me. It was the Ramsays’ darkroom, with trays in which negatives from films under production would be developed and the photos hung to dry. It was like a secret room away from the chatter of the outer office. The red lighting cast a surreal glow on the black-and-white stills of menacing monsters and their hapless victims. I would inevitably make my way there and bravely pore over each photograph, each scarier than the last. Alone, I could barely spend a few minutes there before darting back to the comfort of the soothing daylight and my uncles’ avid discussions of the ongoing or upcoming productions.

Actors and actresses would come in for their story sittings. Technicians, music directors and whomsoever was involved with the films frequented the office. Plates of boiled eggs garnished with salt and pepper were offered to visitors and a grated apple milk drink or watermelon juice served as the thirst quencher. These were in uninterrupted supply because the vendors ran their business at the office doorstep. There were always some people hanging around outside, trying to catch a glimpse of the action taking place inside. I felt very privileged that I could walk in and out as I pleased and not be stuck in the sweltering heat like the curious bystanders were. As soon as I opened the office door, jostling onlookers would attempt to peek inside the mystery that was the Ramsays.

ALSO READ: Resident Evil: The Zombie Apocalypse In Goa

Casually lying around were terrifying masks of ghouls, monsters and witches. I still remember the smell of the latex rubber as I tried them on and scampered around the office trying to spook everyone and being a pest. The one thing I can say about my maternal family is that they were unfailingly kind and gentle, amused at my antics. Finally, exhausted and hungry, I would make my way up the stairs to the family residence, where my grandmother waited with a big smothering hug, a paper dosa and sheera from the neighbouring Ramanjaneya restaurant.

I also went for a couple of location shoots and saw the Ramsay monsters upfront, but I would barely bat an eyelid. Watching an actor turn into a fiend from scratch was not particularly frightening. When the film was ready, the Ramsay clan got to see it in all its gory finality. The same monsters, who were not so fearsome during the shoot, were so petrifying that I would have nightmares for days on end. That was the high! That hair-raising moment where you don’t want to look at the screen, but you can’t look away either.

The intoxicating rush of terror stayed with us, and so my mother and I devoured horror films over the years. That was our link to each other and to her family. In the course of our binge-watching, my mother and I suggested that her brothers watch a suspense film we had enjoyed. They did, and the story captured their imagination. An adaption followed—Telephone, one of the rare Ramsay Brothers murder mystery movies. Regretfully, like my childhood, it all ended.

My grandparents passed away. Their beds touching each other lay empty. The brothers ultimately went their separate ways. The overgrown sisal tree that my grandfather had planted now covers the naked desolation of the building at Lamington Road. Their films released and faded into oblivion. The office remains locked with the eroded Ramsay Films banner holding on to the past. That era of horror is over, and only the memories and movies remain.

ALSO READ: An Allegory Written In Blood

My mother, Asha, whom my father affectionately calls ‘horror sister’, missed her calling. While narrating her supernatural experiences for this book, she would excitedly add dramatic elements of horror: “Why don’t you say that her nails were dripping blood?” or “Her eyeballs turned upwards!” I would have to keep reminding her that I was writing true accounts of the experiences, not a Ramsay script. Even though she understood that the book is about staying authentic, old habits die hard. I had to be a strict taskmaster to keep her narratives from straying into fiction.

But in these moments, it struck me that horror was in my mother’s genes. She could create such scenes with a snap of her finger. Her eyes would shine as her imagination soared into the universe of horror. I credit my creativity to my maternal family, predominantly my mother—the original storyteller. The ability to create a world with words is my inheritance. Destiny has driven me from birth along many pit-stops to halt at the eventual destination of this book.

I was born at the precise moment my father was speeding past the Chandanwadi crematorium in south Mumbai, trying to get my mother to the hospital in time. It was just over an hour past midnight when he jammed the brakes of his Ambassador car, BMC 9931, on hearing my new-born cries emanating from the backseat, as I lay cradled in the folds of my paternal grandmother’s sari.

And so, the final resting place of people became my birthplace. While some are to the manor born, I was to the spirits born.

(Excerpted with permission from Alisha Kirpalani’s Ghosts in Our Backyard published by HarperCollins.)

ALSO READ

Alisha ‘Priti’ Kirpalani is an author and granddaughter of F.U. Ramsay