Spiritual gurus or babas are believed to possess unique healing powers and are usually popular among those who are socially deprived and economically insecure. Many gurus and babas play a positive role in the lives of their followers by delivering charity to the needy or by providing the marginalised with hope. Many flock to these godmen because they believe that mainstream politics and religion have failed them and as a result of this, many gurus and babas end up having an astonishing number of followers.

Some of the deras in Punjab/Haryana—mainly Dera Sacha Sauda, Sirsa, Dera Radhasoami, Beas, and Dera Sach Khand, Ballan—have been generating social capital for the empowerment of historically disadvantaged sections of society. In French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s words, it is a “durable network of more or less institutionalised relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition.”

Social capital emanates from varied socio-religious and cultural networks, and norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that exist in the relations among persons. It is not located ‘either in the actors themselves (like less tangible human capital, which is embodied in the skills and knowledge acquired by an individual) or in the physical implements of production (as is the case of physical capital, wholly tangible, being embodied in observable material form).

Nonetheless, though less tangible in comparison to both physical and human capital, social capital enhances the capacity of adherents of deras to excel in their chosen sphere of life by honing their interpersonal relations. American sociologist James Samuel Coleman further defined it ‘by its function’, which manifests itself through different forms within the ambit of ‘some aspect of social structures’—embedded, as mentioned earlier, with extensive trustworthiness and mutual trust.

An amalgamation of both ‘bonding (exclusive)’ and ‘bridging’ (inclusive) social capital networks, some deras have established their own hospitals, educational institutions, technical training centres, provision stores, local transport systems, weekly magazines, and libraries.

The widespread institutional set up of such deras fosters further networks of dense reciprocal social and religious relations amongst their followers. Daily routine darshan sessions (face-to-face interactions) between the babas/heads of deras and their devotees—an exercise that develops norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness in the relations among followers of deras on the one hand and their baba/guru in the dera on the other—are organised in many deras.

In addition, many deras regularly organise monthly/annual samagams (religious congregations), especially on the birth/death anniversaries of their sants/babas, which are attended by large numbers of their followers as well as notable political figures.

It is during such routine gatherings that their devotees—comprised of all societal strata—generate significant volume of social capital by providing deras with a unique socio-religious and cultural status as well as elements of reciprocity and trustworthiness among themselves vis-à-vis the phenomenon of mainstream religious orders.

Though most such relationships are formed among the marginalised and historically deprived sections of society, their sheer number, measured in terms of electoral arithmetic, generates a rich haul of ‘bonding social capital’ that works like “a kind of sociological superglue,” argued American political scientist Robert Putnam.

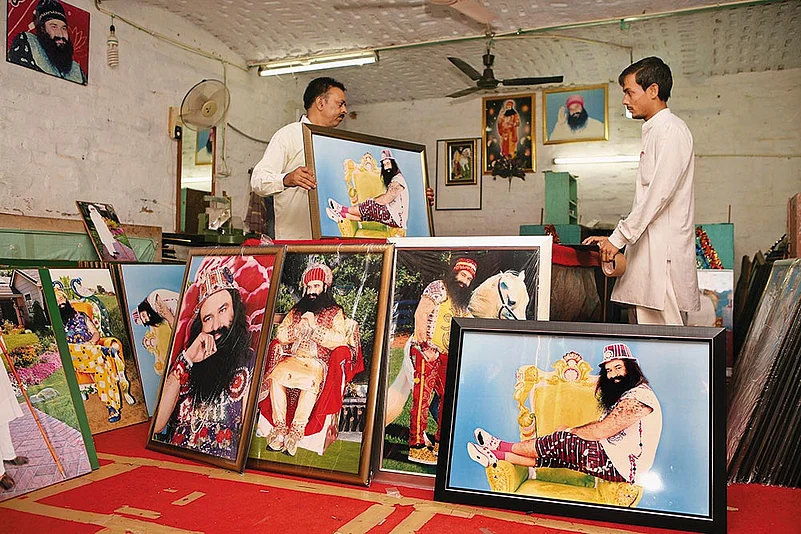

Deras have gained unique profiles over the course of time with the adoption of distinct rituals, ceremonies, traditions, slogans, symbols, auspicious dates, customs, ardas (prayer), kirtan (musical rendering of sacred hymns), religious festivals, iconography, and attire of babas.

Distinct identity markers meticulously devised by the babas of deras are what Devine & Deneulin called ‘the moral code’ of an emerging alternative socio-religious samaj (society), which together with mammoth physical infrastructure, form a viable agency of upward social mobility for socially discriminated and economically poor sections of society.

These informal sets of norms and values, which seamlessly bind together followers of deras, were chiselled over extensive periods of time within the compounds of deras wherein congregations were, and are, perennially regaled by announcements against drug abuse, female infanticide, dowry malice and communal vilifications, before the main spiritual discourses are delivered.

This has resulted in believers gradually internalising a common code of ethics, which congealed them further still with the dera culture eventually leading to, what American political scientist Francis Fukuyama cogently argued, ‘constituting social capital itself’. Socially charged spiritual discourse “… offers a kind of moral compass to help people live their lives in a proper manner” with the purpose of facilitating believers in realising their maximal potential—an outcome of the social capital of deras.

The diverse followings of deras propel people of different castes, classes, creeds, genders, status, and regions not only to bond together (in the form of a bonding/exclusive social capital networks) on the premises of deras on special occasions, but also cultivate long-term inter-community relationships (bridging/inclusive social capital networks) within their neighbourhoods for feasible mutual empowerment.

All activities within deras, including cleaning work, administration, security arrangements, managing traffic flow on both public and dera roads during dera events, and langar (which is free food offered to visitors irrespective of their caste, class and creed) preparation and distribution are all managed by sevadars (volunteer workers drawn from dera members)—who thereby become de facto ambassadors of deras’ social capital.

Dispatching such work is no mean feat since at times the number of visitors comes close to a million, especially during annual bhandaras (yearly religious congregations to pay obeisance on the anniversaries of the founders of the faith).

The aforementioned institutional infrastructure, together with the diverse bonding social networks of deras and their emphasis on social values—such as leading a truthful life, earning by the sweat of one’s brow, respecting mainstream religions, non-discriminatory behaviour, and egality—are what generate the immense tangible and intangible social capital, also called ‘sacred surpluses’, which further boosts the mass appeal of deras through a progressive social spiral. However, there is a downside—social capital—cautioned Putnam. It “may also create strong out-group antagonism”, and eventually snowball into outright conflict formation.

Taking a cue from Coleman’s explication of social capital as discussed earlier, it can be safely argued that deras represent ‘some aspect of social structures’, which precipitate behavioural changes among their followers, thus facilitating the performance of various functions, including mass manual labour that, in turn, inculcate what Putnam called ‘norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness’, mutual respect, and truthful behaviour, eventually leading to the creation of a significant mass of social capital.

Other than dera-based social structures promoting such virtues as trustworthiness and mutual respect within the tangible physical boundaries of such deras (bonding social capital), they also influence the formation of social, community, and family ties between followers in the form of marriage alliances and other close social associations across caste, class and creed divides (bridging social capital).

Coleman further explicates that social capital makes ‘possible the achievement of certain ends that in its absence would not be possible’. It is in this crucial context that deras are distinguishable from other social constructs such as cooperative societies, sports clubs, ethnic groups, literary associations, self-help groups, cultural bodies, environment protection organisations, and varied social reforms organisations.

The phenomenon of deras needs to be studied from the perspective of their contribution towards the generation of social capital—and the emancipation and empowerment of lower caste and middle-class people in particular—and the unfortunate but seemingly inevitable formation of social conflicts as an outcome of the political economy of religion.

In the face of insidious and ever-creeping structures of social and economic discrimination, especially since the onset of a neo-liberal regime in the early 90s, the poor and lower castes became increasingly disempowered in the competition for well-paid private sector jobs.

Deprived of due representation in the corporate sector on the one hand, and with dwindling job opportunities in the public sector on the other, these socially and economically isolated sections of the society turned en masse towards deras, which administered a balm by way of the egalitarianism, health, and education facilities provided by them—i.e., the tangible social capital.

Therefore, a major attribute of deras is their capacity to provide succour to those tossed aside by the mainstream, providing in some form what in more developed countries would be offered by such professional services as marriage counsellors, psychologists, and caregivers. Indeed, to draw an unorthodox parallel, the social capital alchemised by deras likely achieves a far stronger bonding, and amongst far more people, than what companies aim to achieve with their team-building excursions and exercises.

The social and material support structures generated by deras can be illustrated by a triangular matrix consisting of followers from everyday walks of life, politicians, and both the babas of deras and their managerial staff. Different categories of people visit deras for the fulfilment of respective socio-religious and psychological traumas created in the majority of cases by economic deprivation and social discrimination.

The ever-increasing strength of dera-followers makes the cultivation of deras a compulsion for the second component of the triangular matrix, i.e. politicians. The babas of deras and their managerial staff, the third node of this triangular matrix, play a crucial role in keeping their following intact among the populace and politicians by projecting their enhanced prestige and importance within corridors of political and administrative power-circles.

The modus operandi to build up the popularity of deras is based on intertwining myths about the unlimited spiritual powers of such babas with their proximity to centres of power within the civil, business, and administrative domains to create a ‘power-halo’ effect.

All three aspects of this triangle—babas, followers, and politicians—therefore mutually reinforce each other, with political parties practicing outright hard-headed realpolitik by viewing massive dera followings as potential vote banks, and therefore a good investment in terms of political patronage. This proximity to political power, and perceptions of individual deras’ political affiliations, in turn, play a significant role in raising their profiles and hence followings. Thus, a paradigm of mutual reinforcement becomes operative.

Babas of deras are not mere mortals but rays of divinity in the eyes of their followers. During the regular satsangs (sacred congregations for spiritual discourses) on the premises of the deras, it is repeatedly emphasised that babas/gurus are physical links to a formless God and it is only through them that devotees can meet God or more readily resolve their worldly woes and realise their aspirations.

It is emphasised in the sacred texts of Sant Mat (path of truth/ true teachings of the bhakti sants) literature that the spiritual utility of a guru resides in the invisible form of a shabd guru (spiritual sound), which can only be experienced by meditating on the guru or baba’s image while silently reciting the sacred naam (holy word) shared by the guru at the time of initiation. Thus, in the terrestrial world, the guru or baba is indissolubly intertwined with the shabd guru which is the physical manifestation of God, and God himself.

Devotees are implicitly groomed to avoid criticism of their babas/gurus since they are cast as causal linkages to God and transcendent of worldly cares and mores. Such deeply-instilled sentiments are what motivated thousands of followers of Baba Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh Insaan, chief of Dera Sacha Sauda headquartered in Sirsa, Haryana, to camp in Panchkula’s Sector 23, turning it into a mini-Malwa of Punjab for three days—until the verdict of his decades-old rape case was announced on August 25, 2017.

Subsequently, they created a state of anarchy in the area around the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) court in Panchkula once their baba was convicted and was being taken into Haryana Police custody for the announcement of the quantum of punishment.

Despite the deployment of a huge posse of police and paramilitary personnel for the maintenance of law and order, mob violence erupted within three hours of the announcement of the verdict, killing and injuring a large number of people. It is in such precarious contexts that the social capital of deras can mutate into what Putnam called “malevolent, antisocial purposes, just like any other form of capital”, which consequently gives rise to conflict formation in society.

(This writeup is a part of a larger study under preparation)

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Ronki Ram is currently Shaheed Bhagat Singh Chair Professor of Political Science at Panjab University, Chandigarh

(This appeared in the print as 'Decoding The Deras')