Back in 2007, it came with all the accumulated joy of an old dream being realised. Mayawati was taking oath for the fourth time as CM of India’s most populous and political state of Uttar Pradesh—this time with a majority unprecedented for any Dalit party. It seemed like Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s dream of a self-sustaining Dalit politics, which he initiated in 1936 by founding the Independent Labour Party (ILP), was finally bearing fruit. Mayawati’s rise was ascribed to the Bahujan Samaj Party’s ideology and its founder Kanshi Ram’s vision.

Mayawati’s victory seemed like a decisive inflection-point in Indian politics—it filled Dalits across the country with great pride and elation, and created a great reverence for Mayawati among them. Outside estimations reinforced the Iron Lady halo. She was even seen as a potential prime ministerial candidate by observers and other parties alike. In 2007, she was on Time magazine’s list of 15 most influential persons of India and among Newsweek’s top woman achievers. In 2008, she joined the likes of Angela Merkel and Sonia Gandhi in the Forbes list of the world’s 100 powerful women. The Independent, London, called her “unstoppable.”

In ten years, the narrative has inverted almost entirely. Her party drew a blank in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. And now, the BSP has plummeted to a mere 19 seats in the 403-seat UP assembly. Juxtapose that number with the 206 seats she won in 2007 to see how steep the fall has been. Whether she would make a perfect tragic figure, whose misfortune is brought about by an innate flaw, is an open question. But her fall presages a wider tragedy for Dalit politics, which must be understood and fought.

Independent Dalit politics, to which Mayawati claims a legacy, started with Ambedkar’s idea of electoral representation for untouchables, based on the population percentage, as early as 1919. For the next 17 years, Ambedkar worked on making untouchables a political force, in the face of Mahatma Gandhi’s opposition. In 1931, Ambedkar and Gandhi clashed in London on the issue. Ambedkar won electoral representation by means of reserved constituencies with separate electorate in 1932, only to be thwarted by Gandhi by a fast unto death in Poona’s Yerwada Jail.

Gandhi succeeded in tweaking the formula for representation, changing it from a separate electorate to a common electorate of all Hindus voting to elect a Dalit representative to the legislature. This arrangement was formalised by the Poona Pact, signed on September 24, 1932. Thus, every Dalit legislator in a reserved constituency is elected by the votes of the entire electorate there. Looking at the impending elections of 1937, Ambedkar created the ILP and won 15 of the 17 seats it contested in the Bombay Province. The first elected Dalit legislator appeared thus in 1937, solely a creation of Ambedkar’s unrelenting efforts.

Ambedkar’s politics of 1937 took up the cause of both industrial and agricultural labour, akin to the Dalit-Bahujan politics Kanshi Ram crafted decades later. Ambedkar engaged in continuous agitational politics. In 1937, he mobilised 20,000 agricultural peasants in Konkan in favour of the Zamindari Abolition Bill. On the issue of the Industrial Disputes Act, he joined forces with the Communists, ensuring a big strike in Bombay’s industrial mills in 1938. He fought for the abolition of Mahar Watan, a traditional village servitude of Dalits.

By 1942, Ambedkar realised Dalits had become politically conscious and created a new party, the All India Scheduled Caste Federation (AISCF), solely focused on taking up the cause of untouchables further in the run-up to independence. The ‘Elephant’, later claimed by the BSP, was originally the AISCF’s electoral symbol.

Ambedkar never went in electoral alliance with the Communists and the Peasants and Workers Party. He did join hands with the Socialists—which Kanshi Ram too did, by tying up with its ideological legatee, the Samajwadi Party, for the 1993 elections in UP. Ambedkar was highly critical of the RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha, the ideological progenitors of today’s BJP. He called them retrograde organisations.

The AISCF contested the 1946 elections and independent India’s first in 1951 and was a failure. It could not even garner enough seats in 1946 to send Ambedkar to the Constituent Assembly. But he used it as an organisational bargaining platform with the Congress, which came to power, to gain rights for the oppressed. He even joined the Nehru government to work towards ensuring the rights of Dalits, backwards and, more so, women.

Ambedkar’s AISCF could not achieve the peaks that Kanshi Ram and Mayawati attained five decades later through the BSP. Nevertheless, Ambedkar had created the very space for organised Dalit politics. Not only that, he largely succeeded in capturing the imagination of Dalits, spurring them on to achieve political power by organising themselves into a party. After 1950, by virtue of universal adult franchise in a democracy, they became a numerical force to reckon with.

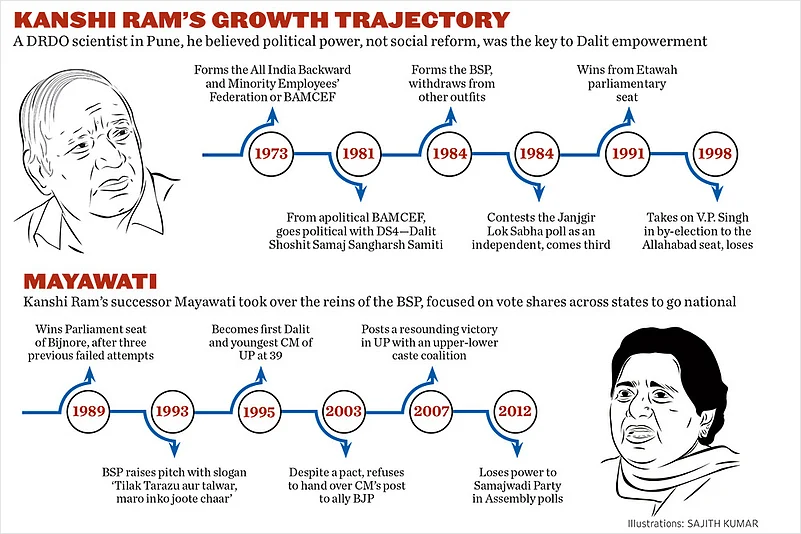

Before his death, Ambedkar conceived of the Republican Party of India (RPI), which came into being in 1957. The RPI tended to the task of organising Dalits and was active in Maharashtra, UP and Andhra and returned some seats in assembly and Lok Sabha polls in the first three decades after independence. But Dalits were still largely with the Congress. By the late 1970s, the RPI had suffered an amoeba-like fragmentation into several parties, when Kanshi Ram entered Pune and created BAMCEF (All India Backward and Minority Communities Employees’ Federation) in 1978, quietly learning his lessons from the RPI’s failure and its limitations.

The RPI’s fragmentation had created a political vacuum in India. It was at this juncture that BAMCEF arrived to fill this void. BAMCEF got involved in creating a Phule-Ambedkarite consciousness aimed at bringing a radical social transformation. Kanshi Ram was an organiser and sought to realise, in practical ways, the aims of an ideological movement encompassing the whole Dalit-Bahujan canvas. He saw this umbrella definition as covering 85 per cent of India’s population, including Dalits, backwards and minorities, against the 15 per cent elite castes who ruled over them.

Kanshi Ram painstakingly built BAMCEF, later started DS4 (Dalit Shoshit Samaj Sangharsh Samiti) and then moved into formal politics by launching the BSP in 1984. Such a political outfit was a challenge to all traditional parties, which could be defined as institutions of power based on caste hierarchies. Shattering this, the BSP made Mayawati the first Dalit chief minister of UP in 1995, when Kanshi Ram was just 61 and she only 39. In a critical tactical move, the BSP ditched the socialist SP and took the BJP’s support, and repeated the experiment thrice.

Kanshi Ram, with his band of dedicated, tireless workers, took the BSP from 9.4 per cent votes in 1989 to a high of 23 per cent votes in 2002. The party made a sustained campaign for the implementation of the Mandal Commission throughout India, aiming at a pan-India following. Some backward castes had remained under-represented since independence in every sphere. The BSP gained their confidence and over time prised out Dalits and MBCs from the Congress mosaic, which was already shattering as the SP pulled away Yadavs and minorities.

The Mandal Commission became a decisive tool of mobilisation for the BSP against the BJP’s mandir wave in 1991. When Mayawati won a simple majority with 206 seats and 30.43 per cent votes in 2007, a year after Kanshi Ram’s death in 2006, it was a logical conclusion of the long campaign that Kanshi Ram had spent his life on.

The BSP’s arrival generated hope for the Dalits and backwards—at last they would finally realise their political potential. The BSP, forged in the furnace of a sustained social movement, was now in a position to make it happen. But an election victory won on its own instilled a different spirit—it brought about a new behaviour in the rank and file of the BSP, including the leadership. After Kanshi Ram’s death, the means and the end switched places. Gradually, the Dalit-Bahujan movement turned into an instrument for Mayawati to purely seek and retain power. Kanshi Ram was a Dalit-Bahujan movement person who used the tactics of electoral politics for his larger purpose; Mayawati became a pure vote aggregator. Her politics gradually ceased to create the emancipatory atmosphere of Ambedkar and Kanshi Ram.

As an institution, the BSP survived as a strong presence in the minds of its supporters but the leadership as well as the rank and file grew deaf and intolerant to internal dissent and became extremely self-centric. There was hardly any public contact programme or cadre recruitment drive, little thought was given to organisational structuring. The top leadership became dead to the one real need of a live political party—open ground-level communication—at a time when it could easily fulfil it.

Mayawati’s parks and statues afforded limitless opportunities for the opposition to criticise her. In actual fact, the parks and statues were aimed at creating a new, alternative cultural discourse and narrative. (The Sardar Patel statue and Shivaji memorial projects, for instance, are more than five times bigger in terms of investment compared to Mayawati’s budget). Where she lost the plot was in bringing her own statues into the parks.

The public perception against Mayawati, already coloured by caste, grew as she did not deem it necessary to communicate. The result was a very big disaster in the subsequent election. The BSP’s decline in north India in recent years ranges from the notable to the breathtaking. Delhi: from 14.05 to 1.3 per cent; Haryana: 6.73 to 4.37; Punjab: 16.32 to 1.5; Bihar: 4.41 to 2.07; Rajasthan: 7.6 to 3.37; Himachal: 7.26 to 1.71; Madhya Pradesh: 8.97 to 6.29; Uttarakhand: 12.19 to 7. The number of MLAs in these states has seen a proportionate nosedive. This failure is not that of the Dalit-Bahujan vision of Kanshi Ram, but that of Mayawati’s personality cult and cynical politics. She has completely cut herself off from the Dalit intelligentsia and doesn’t believe in interactions with the media or engaging with Dalit-Bahujan activists. There is also virtually no other leader left in the BSP who was groomed by Kanshi Ram.

Between 2007 and 2017, Mayawati was always busy waiting for the next election rather than sustaining the roots of the movement—that too at a time when political consciousness among Dalit youth was reaching a new level of vitality. She failed to respond to Dalit issues and never joined mass movements that rose organically—missing out on a critical dialogue with the times. Her presence would have energised those movements, while she herself could have drawn sustenance from the fight for rights and power being fought on the streets and the campuses. On the contrary, she was conspicuously absent during the Rohith Vemula and Kanhaiya Kumar episodes, whereas even leaders like Rahul Gandhi and Arvind Kejriwal trooped to Hyderabad and JNU.

She marginally touched upon the Una flogging but mostly failed to visit the spots, or hold protests or lead demonstrations. Remember, this was at a time of an electrifying Dalit mobilisation and march. There was never any attempt to join forces, build coalitions, partake of the energy and help the young activists turn these incidents into a national Dalit movement. She merely waited for the next Uttar Pradesh polls. This is what one means by distinguishing between Kanshi Ram and her—one was a mass movement leader, the other became a sedentary electoral strategist without that vital nutrifying link to the ground. For example, the Muslims, who she tried to aggregate as voters in 2017, commented that she never even visited the Muzaffarnagar riot locations.

Her second failure was a related one. By not creating a second-line leadership, Mayawati remained the sole campaigner; consequently the BSP failed to attract the present-day youth. She would mechanically read out speeches at public rallies, taking her captive audience for granted—a far cry from negotiating live with the new generation. Institutional deaths, UGC regulations, educational discrimination, the nationalism debate with caste at its centre…there was no dearth of opportunity to connect with a wider imagination, tap into the popular wellsprings, but she forfeited all of them.

As Mayawati retreats into her solitary splendour to wait for the next election, she must ponder over her missteps. Electoral politics is not an end but a means to seek equality in an unequal society. We don’t know whether Mayawati, 61 now, will revert to a Kanshi Ram model of mass movements. She probably has an unfinished Ambedkarite dream. Before his death, Kanshi Ram wished to convert to Buddhism; Mayawati was waiting for an opportune time. On the Una issue, she mulled converting in protest, but paused. She can still finish Ambedkar’s unfinished agenda of Prabuddha Bharat, leading Dalits and backwards from the maw of Hinduism into Buddhism. Else, the parks will remain her only legacy.

(The author is professor in Visual Studies, School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU, New Delhi)